(by Phil McMullen) |

|

||

|

In the mid-1960s though the coal mines, oil refineries and steel mills were still ablaze. One way for young men on leaving school to avoid immediate conscription into industry was to grow their hair and join a rock and roll band, and there was already a vibrant scene emerging: Love Sculpture and Amen Corner out of Cardiff, the Eyes of Blue from Neath, the Jets and the Iveys (later to become Badfinger) from Swansea - and from the sleepy South Welsh town of Merthyr Tydfil, a group called the Bystanders.

As with so much at that time, the Beatles had a lot to answer for in terms of the Bystanders’ musical style, and indeed their dress sense, which ran to matching mohair suits with blue knitted ties. Guitarist Micky Jones, an apprentice hairdresser by trade, was given the “cooler sounding” stage name of Mike Steel, and keyboard player Clive John bizarrely reverted to his real name, Clive Morgan. In 1966 they signed to Pye Records (home of the Kinks and the Searchers), incorporated Beach Boys and Four Seasons songs into their stage act, and headed out onto the cabaret circuit.

By 1967 the shock-waves from the explosion of psychedelia in America finally reached South Wales. The ace up the sleeve of the Bystanders, which set them apart from their rivals, was their guitarist. Having been well schooled in rock and roll, Micky Jones was now ready, able and willing to listen to, and be influenced by, more experimental guitar players such as the Grateful Dead’s Jerry Garcia and Quicksilver’s John Cipollina. Although venues like the Camarthen Bay Power Station Recreation Club were a million miles away, culturally speaking, from Marin County or Big Sur, The Bystanders accordingly varied their live set to take in covers of such songs as the Byrds’ ‘Eight Miles High’ and Moby Grape’s ‘Hey Grandma’. They began writing their own material (Jones and John’s ‘Cave of Clear Light’ – “one of the few songs of the period I can still listen to without wincing”, according to Clive John – reveals fashionable middle-eastern influences) and, in November 1968, they shuffled their line-up, brought in second guitarist Roger “Deke” Leonard and changed their name to Man. Progressive rock was becoming the dominant force. I was ten years old at the time.

It’s funny how a profound an effect an unexpected and at the time seemingly insignificant incident can have. I was stood at a bus-stop not so long ago next to a beautiful girl who had a smile like the wires strung between two pylons; wide, curving and powerful enough to melt your shoes into the ground if you dared get too close. All too soon she was gone, who knows to where: but in my head at least we went there together, on the top deck of a bus with the breeze ruffling her blonde hair, her breathtakingly attractive eyes gazing into mine and the noise of the engine carrying her golden voice away like leaves on a swollen river. I was reminded of an earlier event which had quite literally changed my life forever.

I was 10 years old, and the blonde on the bus this time attended the same school as me. She announced to anyone who’d listen that her uncle was in a pop group called Man, who quite frankly I had never heard of. Then again, given that we lived in a remote rural location I sadly lacked exposure to anything approaching culture during my formative years. Even by 1968 psychedelia had yet to reach Somerset: the first Glastonbury festival was still some two years away, taking place in September 1970 on the fields of Pilton Farm, organised by dairy farmer Michael Eavis.

I worked backwards and scored copies of every other LP I could find by Man. From reading interviews with them in music papers and magazines I discovered that they in turn had been influenced by a band called Quicksilver Messenger Service. I bought their records and immediately fell in love all over again. Man toured with a band called Help Yourself. I bought their records and immediately fell in love all over again. I was a fickle teenager when it came to affairs of the heart. I bought United Artists Records’ ‘All Good Clean Fun’ double LP compilation because it featured songs by both Man and Help Yourself and through that discovered other fine underground bands like Cochise and Hawkwind, Can and Amon Duul II, which opened a whole load of new doors of perception and in turn led me to German music. In short, I owed my entire early musical education to the Man band. Through them I discovered west-coast American psychedelia and down-home English country rock, and indirectly I discovered folk-rock and kraut-rock. Most of all though, through Micky Jones’ guitar playing I discovered an abiding admiration for improvisation.

When Man had emerged, phoenix-like, out of the Bystanders in 1968, swapping increasingly psychedelic harmony pop for full-on progressive rock, they quickly discovered that their future lay overseas. Faced with playing to an average audience of 20 people in England or 200 in Germany, they began a campaign of saturation-gigging over there. As keyboard player Clive John explained: “There was a tremendous feeling of musical freedom. You could easily get away with playing a flower pot on stage in Germany in those days. We were listening to people like Stockhausen at the time. The band was spaced out, but the music was really interesting.” Deke Leonard: “In Britain we were expected to play for two hours – but Germany expected five hour sets, so we stretched what we had.” The key to all this extended jamming was of course improvisation - and in Micky Jones they had a master of the craft.

Deke Leonard, again, speaking recently: “Micky’s the best improvisational guitarist in the world. I’ve played with him for 30 years now and once he goes into an improvisation I’ve never heard him play the same thing twice. It would be so musical, so structured and beautifully laid out, that you’d think he’d worked it all out – but we’ve shared rooms and nobody ever took their guitars into their hotel room. It just all came pouring out of him.”

The Man band were always at their zenith in the live setting, therefore their studio albums aren’t always representative of what they could achieve: the self-titled LP for United Artists in 1970 for instance suffered through having to condense their everlasting jams from lengthy shows in Germany down into fifteen or twenty minutes. Thereafter they gave up trying to capture their live sound in the studio and instead concentrated on the job in hand, with one honourable exception: the aforementioned 1972 album ‘Be Good To Yourself At Least Once a Day’, during the recording of which tensions within the group were allegedly running high following a line-up shuffle. Deke Leonard had temporarily left to pursue a solo career, the new guys in the band had brought a backlog of songs with them that they were keen to try out, but they met with considerable resistance from Micky Jones, who preferred the group to improvise new material. Clive John suggested a pragmatic new approach: “Let’s just forget we’re supposed to be making a record and have an electric blow”. The result was a four-song set with a strong instrumental bias which gave Micky Jones’ guitar work and songwriting style completely free reign. It remains arguably Man’s finest moment and included two songs, ‘C’mon’ and ‘Bananas’, which according to Deke Leonard, “Will still be in the set when we play that final celestial set in paradise... we’ll probably open with ‘C’mon’.”

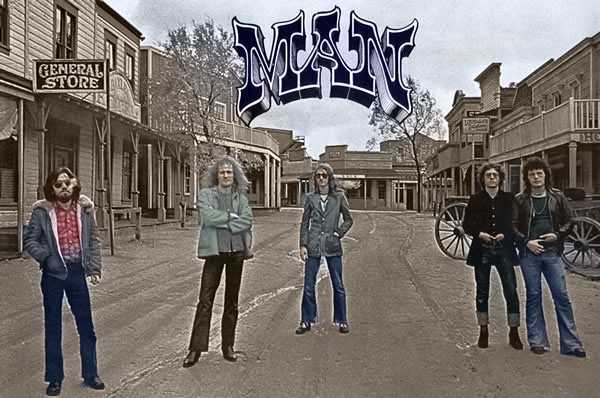

Photo: Man photographed in San Francisco. L-R Terry Williams, Ken Whaley, Deke Leonard, Micky Jones

Man called it a day in the mid-seventies, culminating in three dates -appropriately enough at the Roundhouse again - during December 1976. They had released fourteen albums and had been through nearly as many line-ups, the one constant member being Micky Jones. “During the last year we had found little to agree upon”, opined singer/guitarist Deke Leonard, “but the one thing we were all sure of is that we would never, ever be one of those bands who re-formed in a futile attempt to recapture past glories and maybe earn a buck or two along the way.”

They re-formed on All Fool’s Day, 1983. By that time my own life had moved on and I never again followed the band with quite the same interest; the love affair was far from over – in fact, I’d claim Man’s performance at the Terrastock 3 festival in London during August 1999 to be one of the single most captivating, emotionally moving and powerful live shows I’ve ever experienced – but, if pressed I’d have to admit that I stopped working quite so hard at our relationship after Man broke up in 1976. I’m quite sure the Man band felt the same way about me too, had they actually known who I was.

Micky Jones formed a tight little three-piece rock band named Manipulator after leaving the band. They played a mixture of Man material, such as ‘Kerosene’ and ‘Breaking Up Once Again’, in amongst new songs and covers, including Buzzy Linhart’s ‘Talk About a Morning’. I saw them several times and they never failed to deliver the goods; compact, raunchy and powerful, they were the very antithesis of the jamming juggernaut which was the Man band and yet still a great vehicle for Jones’ fluid guitar work. It was at one of Manipulator’s gigs, at the Half Moon in Herne Hill in October 1980, that I met another person who was to change the entire course of my life: Nigel Cross.

Nigel had recently launched a new fanzine called ‘A Bucketfull of Brains’, and was there to interview Micky Jones for the upcoming third issue. Deke Leonard had been featured in issue 1 (along with American acts Television and Michael Hurley), and a mutual acquaintance had recommended my name as a possible expert on the subject of the Man band. Nigel phoned me to ask if I’d like to sit in on the Deke Leonard interview. I would like to! Very, very much indeed, thankyou!

“It’s taking place here in London on Friday.”

“Great! Oh, wait - shit, I have a job interview that same afternoon...”

“OK, well maybe next time then...”

Having idolised the Man band from afar for the majority of my formative years I never thought there’d be a first time let alone a second one, so it was fairly easy to shrug that one off. Then the ’phone rang again.

“It’s Nigel again. Sorry... I was wondering if I did the interview with Deke, if perhaps you’d be able to transcribe it for me?”

“What, you mean write it up?” I said, proud of myself for having slipped so quickly into the easy argot of the professional Music Critic. “Of course.”

I tried to hide the bitter disappointment from my voice at not having been able to attend in person and settled back to await the arrival of the cassette tape, which sure enough turned up a few days later.

I don’t honestly remember a great deal now about what actually passed between Nigel and Deke during the interview. There was an incident when Deke Leonard disappeared off to the lavatory, still talking. A distant tinkling noise. More words. The sound of a flush, followed by Deke’s soft Welsh voice slowly growing louder as he drew closer to the microphone again. I faithfully wrote down every word, every tinkle. It was my first ever assignment as a music journalist, and I was completely hooked. I knew that someday I wanted to publish a fanzine, just like Nigel Cross.

I mailed the piece off more in hope than expectation, never really expecting to hear from Nigel again, and received by return of post a rather surprising offer to write more: as much as I possibly could, in fact. Maybe I’d like to write some reviews? And could we meet up at the Manipulator gig in Herne Hill a few weeks hence?

We did meet, and Nigel reassured me that I could not only write, but that I could write well. Ha. That was one in the eye for my former school-teachers. I became a regular contributor to ‘Bucketfull of Brains’. Over the years since I have met, spoke to or corresponded with just about every musical hero I’d ever had, and made a thousand more. I ended up running my own magazine, and – I’m more proud of this than anything else, I think – engaged the services of Nigel Cross and, on one famous occasion, even Deke Leonard as contributors.

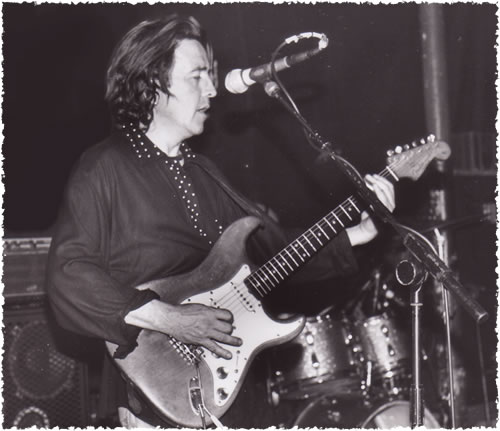

Photo: Micky Jones photographed by Mike Ware

In 2002 Micky was diagnosed with a brain tumour. He left the Man band temporarily to receive treatment for his illness. At the time it was understood to be benign, and it was hoped that following appropriate surgery he would make a full recovery and return to the stage. He returned briefly in 2004, but in 2005 required further treatment, and despite constant efforts has suffered a steady decline thereafter.

Micky Jones finally passed away on 10th March 2010. He was just 63 years old. We've lost a wonderful guitarist - one of the world's finest - but much more than that, we've lost a friend, an inspiration to many and a hero to a few(myself included). Rest in peace, Micky.

Phil McMullen, March 2010

Portions of this eulogy were originally published in Penny-Ante Book #2, San Francisco USA in 2007. |

|||

that in order to understand the Welsh, you first must gain a

sense of Wales. Unfortunately there are almost as many

different colourful facets to the principality as there are

people: in the south alone blue mountains rise from green

valleys to hug the clouds, silver light drifts across

granite castles, white cottages pepper the landscape and

grey seas nibble at the coastline. What the tourist guides

often fail to mention however is that this is also a

landscape scarred black by the ravages of coal mining and

tainted red by the rusting hulk of iron foundries. Where

Ireland often gives the impression of having moved directly

from the eighteenth century into the twenty-first without an

industrial age in between, South Wales today still wears a

curtain of steel. It’s an increasingly thin curtain in this

post-industrial age, but the signs are all around

nonetheless.

that in order to understand the Welsh, you first must gain a

sense of Wales. Unfortunately there are almost as many

different colourful facets to the principality as there are

people: in the south alone blue mountains rise from green

valleys to hug the clouds, silver light drifts across

granite castles, white cottages pepper the landscape and

grey seas nibble at the coastline. What the tourist guides

often fail to mention however is that this is also a

landscape scarred black by the ravages of coal mining and

tainted red by the rusting hulk of iron foundries. Where

Ireland often gives the impression of having moved directly

from the eighteenth century into the twenty-first without an

industrial age in between, South Wales today still wears a

curtain of steel. It’s an increasingly thin curtain in this

post-industrial age, but the signs are all around

nonetheless.  From

filing away in the Rolodex of my mind

From

filing away in the Rolodex of my mind In

1974 Man travelled to America. Initially supporting United

Artists label mates Hawkwind, the tour proved to be eventful

to say the least, with tornados and live telephone link-ups

to LSD guru Timothy Leary amongst their adventures. The band

worked themselves slowly across to San Francisco where Bill

Graham, at the time one of America’s foremost rock

entrepreneurs, took to Man every bit as warmly as he had all

the bands he had promoted in the 60s – bands who had in turn

served as influences for Man in their early days. At the

Winterland John Cipollina, Quicksilver Messenger Service’s

mercurial guitarist, jammed with them on stage; it seemed a

marriage made in heaven, Cipollina’s unmistakeable vibrato

style working so well within the Man context, with Micky

Jones’ fluid lines bouncing off the razor-sharp shards of

Cippolina’s chops while Deke Leonard churned away with his

wah-wah. In fact when a series of live dates in the UK

culminated in a live album named ‘Maximum Darkness’,

recorded in May 1975 at the Roundhouse, John Cipollina’s

guitar parts on Man’s anthemic ‘Bananas’ had to be

overdubbed – ironically enough by Micky Jones. “Everything

on ‘Maximum Darkness’ which sounds like Cipollina is

Cipollina”, according to Deke Leonard, “Except for ‘Bananas’

during which he insisted on playing a pre-war Hawaiian

guitar, with pre-war strings, with a kitchen knife. It was

an appalling racket.”

In

1974 Man travelled to America. Initially supporting United

Artists label mates Hawkwind, the tour proved to be eventful

to say the least, with tornados and live telephone link-ups

to LSD guru Timothy Leary amongst their adventures. The band

worked themselves slowly across to San Francisco where Bill

Graham, at the time one of America’s foremost rock

entrepreneurs, took to Man every bit as warmly as he had all

the bands he had promoted in the 60s – bands who had in turn

served as influences for Man in their early days. At the

Winterland John Cipollina, Quicksilver Messenger Service’s

mercurial guitarist, jammed with them on stage; it seemed a

marriage made in heaven, Cipollina’s unmistakeable vibrato

style working so well within the Man context, with Micky

Jones’ fluid lines bouncing off the razor-sharp shards of

Cippolina’s chops while Deke Leonard churned away with his

wah-wah. In fact when a series of live dates in the UK

culminated in a live album named ‘Maximum Darkness’,

recorded in May 1975 at the Roundhouse, John Cipollina’s

guitar parts on Man’s anthemic ‘Bananas’ had to be

overdubbed – ironically enough by Micky Jones. “Everything

on ‘Maximum Darkness’ which sounds like Cipollina is

Cipollina”, according to Deke Leonard, “Except for ‘Bananas’

during which he insisted on playing a pre-war Hawaiian

guitar, with pre-war strings, with a kitchen knife. It was

an appalling racket.”  This

isn’t about me though: it’s about Micky Jones. Either

directly or indirectly I owe to him almost everything I’ve

achieved.

This

isn’t about me though: it’s about Micky Jones. Either

directly or indirectly I owe to him almost everything I’ve

achieved.