Andrew Lauder Q and A by Ian Fraser (Edited highlights of this interview were originally published in Terrascopædia magazine issue 22, March 2024) Each

of us can probably point to one or more rec And for that we can thank Andrew Lauder, A and R man extraordinaire and surely one of the most single important people in alternative rock music history. Terrascope was pleased to speak at length with Andrew (who, these days, lives in France), following the publication of ‘Happy Trails - Andrew Lauder’s Charmed Life and High Times in the Record Business’. This compelling memoire details Lauder’s early years working in Denmark Street, then still Britain’s Tin Pan Alley, in the mid 1960s, his tenure with Liberty in the late 1960s, United Artists in the 1970s, through to his time with Radar Records and beyond. Co-written with Mick Houghton (PR supremo to the likes of KLF, Teardrop Explodes, Julian Cope and Echo and the Bunnymen - yet more names that make your scribe salivate), ‘Happy Trails...’ reads like a Boys Own compendium of counter-cultural derring-do and jolly japes, underpinned by what seems like almost impossible good fortune and a sense of being in the right place at the right time. I was reminded of the Robert Duvall character ‘Kilgore’ in Apocalyse Now, destined to sail through everything thrown at him without so much as a scratch. Andrew Lauder (AL): [LAUGHS] Yes, I think so, pretty much! That’ll do. Lauder went from being his school’s ‘answer to the Beatles’ (to quote his House master) to a budding Andrew Loog Oldham (they went to the same alma mater) in the space of a chapter break. At what point did he realise that the business end and not the performance aspect of music would be his calling? AL: I think basically when I got to London and managed to get to all the clubs. Working on Denmark Street I was only five minutes’ walk from the Marquee, Flamingo, Studio 51, 100 Club and so on. I realised that these guys were in a different class and were better than I was ever going to be. Having got my first job I soon came to the conclusion that I was better off being around these people and helping them to make records rather than doing it myself. Denmark Street has seen significant change over the years and especially recently. AL: I visited there back in May when I attended the book launch and if I hadn’t remembered the street numbers I wouldn’t have recognised anything. It was all a bit depressing and should have been a bit more preserved, really, especially given its long history and contribution to music publishing from before the Second World War. As a 17 year-old invoice clerk I was in awe of so many people I used to bump into there, the Kinks, David Jones who became Bowie, and who I didn’t much get on with. I think he turned into a much nicer bloke after he became successful but on the way up he was a bit like Marc Bolan upsetting people like John Peel. I guess that it was that determined attitude that eventually got them what they wanted. While Andrew recalls in enviable detail his early working life in and around London’s Tin Pan Alley, his blues and Mod-related gigging experiences and wheeler dealing, there is little or no mention of UFO and the psychedelic London scene of ’66/67. (AL) Actually I was really up for it. I’d go to Indica Bookshop [on Charing Cross Road] in my lunch breaks. This would have been, I suppose, 1966. They had ESP discs and I quickly became familiar with the first couple of Fugs albums. Then I started hearing about the bands that were popping up around London and the early Pink Floyd gigs at UFO. I probably didn’t go that often because from May 1967 I got the job with Liberty and from then on most of the gigs I went to were with Ray Williams, head of A and R, with whom I shared a flat. So I was probably going to fewer gigs because by then we were working on the bands that we’d signed and getting records out and that took up more and more of my time. Therefore I guess that period didn’t impact on me quite as much as ’65 and seeing the Yardbirds and The Who . To the chase, then. Many older Terrascope readers will have cut their musical teeth on a fantastic Liberty/UA sampler entitled ’All Good Clean Fun’. This doesn’t seem to feature in the book. Was this to downplay its significance?

So no, I spent a lot of time on that, including the cover, which was from a Boys’ Own annual from, I think 1895. Originally it depicted a boy sitting in a railway carriage reading a ’Boys’ Own’ paper. However this was at the time of the Oz ‘School Kids’ issue and the trial, and I had this idea of making it contemporary by changing the Boys’ Own into a copy of Oz. There was an antique place near where I lived called ‘The Lacquer Chest’ in Kensington Church Street and they had lots of old magazines and post cards, mostly Victorian, and I thought it would be good to use that for the packaging of ‘All Good Clean Fun’. So, I probably spent more time on this one than the previous two compilations. I was really happy with ‘All Good Clean Fun’. The problem was when we were doing the book we couldn’t put everything in otherwise it would have been like War and Peace! It would have been so big that people wouldn’t want to read it’. It later got the obligatory extended CD reissue. One would hope that Lauder was involved in that. (AL) No, in fact the guy who did it only contacted me when it was all put together and he cursed himself, because aside from the If track, and which I didn’t much care for, I’d been involved in all the other material that they featured. He realised just in time for me to contribute to the liner notes, but I enjoyed it and I think EMI did a good job. A

character who is mentioned frequently throughout this

section of ‘Happy Trails’ is Doug Smith of Clearwater

Productions and who managed bands like Hawkwind, who

would become one of UA’s flagship bands and would help

shape Liberty and UA’s reputation as a home for new

underground bands .

(AL) My friendship with Doug Smith was really important, actually. My friend Wayne [Bardell] and I did High Tide together and then Wayne joined with the two other guys, Richard Thomas and Doug and they had a joint office where Doug lived in Notting Hill Gate. I started spending a lot of time with Doug because I’d just split up with a girlfriend and found myself at a loss. I’d go around to his and have a smoke and listen to records - I was listening to a great pile of records every week which, as head of A and R was a reasonable thing to be doing. Larry Wallis had a band called The Entire Sioux Nation which Clearwater handled and they had Trees (who were already signed to CBS) and High Tide and pretty soon Hawkwind came along .So it was a fun place to go and several nights a week I’d trot over there (it wasn’t far from where I lived). We became really good friends and the first American trip we did together, which was supposed to be a holiday, brought back so much work for United Artists that they ended up reimbursing us for the trip. Doug and I are still good friends and we often keep in touch. He’s living in Spain now. Ironically, Andrew’s label was called United Artists and yet it often seemed to attract bands who couldn’t maintain the same line-up for two consecutive albums. At times it must have seemed like cat herding. Did this help or hinder creativity and was it ‘good for business’? AL - Gosh yes, with Hawkwind you had people coming and going all the time like Bob Calvert and there were two drummers at one point and a succession of bass players. I think Lemmy was their fourth bassist since I’d signed the band. I don’t think that constant regeneration was necessarily good for business but there wasn’t anything you could really do about it. Man,

of

course, were the obvious example, it didn’t really

stop. My own favourite line-up was the two Lauder mentions in the book that his initial impression of Man was coloured by their previous output about which you admit to having been a bit sniffy. Yet he took a leap of faith by signing them without seeing them play. What prompted this inspirational leap of blind faith? AL: The truth is I can’t remember. My earliest memory of actually seeing them was at Rockfield Studios, but I think I’d heard about them so much and I had a good relation with the guys in Germany, where Man played a lot and were popular (they’d even had a hit there) and all the reports that I was getting back were saying how fantastic they were. I was getting on with Barrie [Marshall] the manager and who was obviously determined to make them successful but I really can’t remember how I committed to them, but I’m pleased that I did. Terry Williams was new to the band and made one hell of a difference I think, and he and Martin Ace played really well together. It was that gig at the Roundhouse that made all the difference. I thought they would make an impression, but like a lot of people there I had no idea that they were that good. That Roundhouse gig was of course the ‘Greasy Truckers Party’, a gloriously chaotic fundraiser and which was captured for posterity on a double album release of the same name.

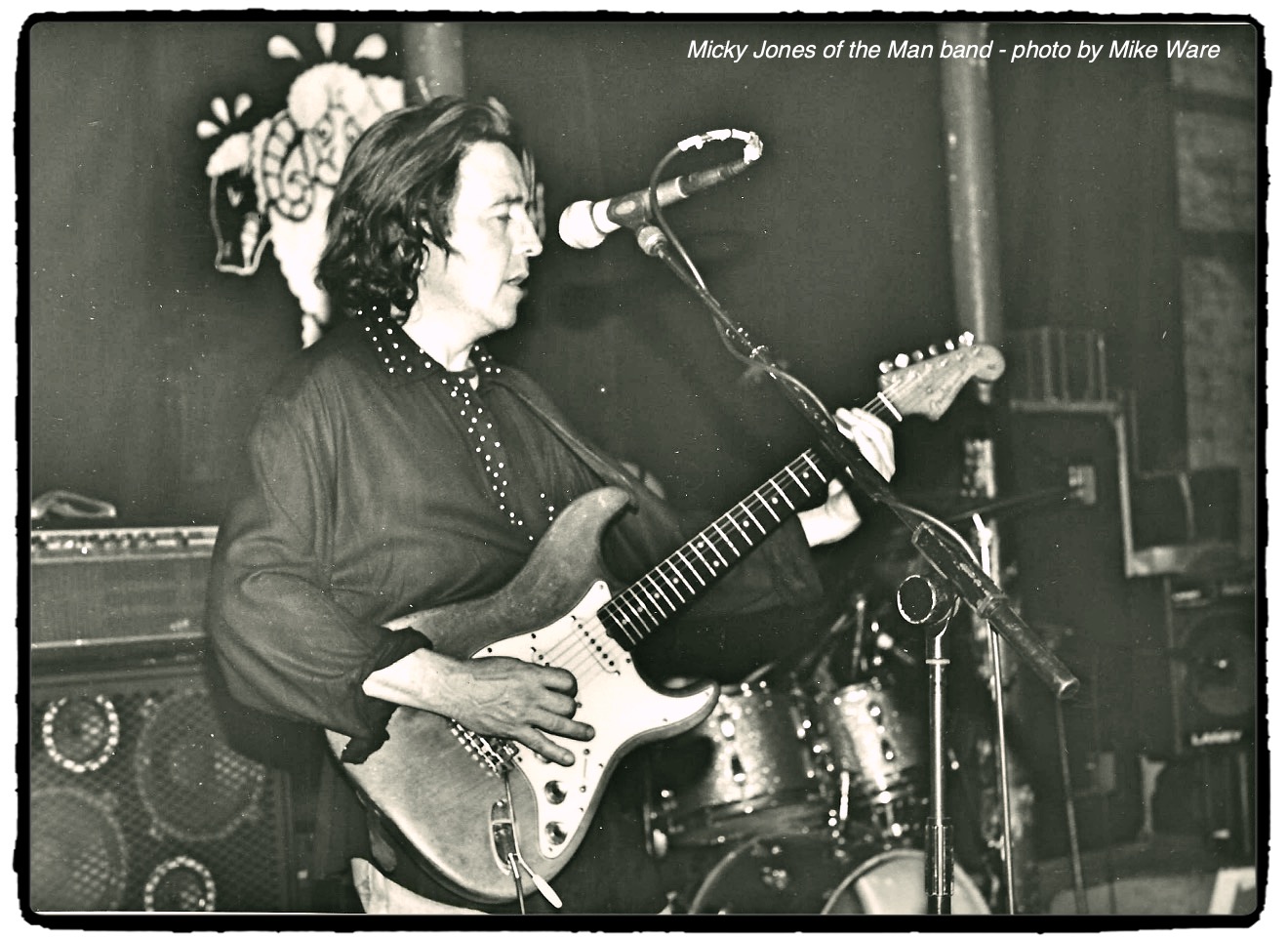

Mention of which prompts the question what did happen to Byzantium? (AL): They were already signed with A & M at the time. I can’t say I ever saw them play live and it was regrettable that they drew the short straw, but I was determined that Man should play and that was my ‘part of the deal’. I don’t think they lasted too much longer after that. Staying with Man, Andrew speaks warmly in the book of their tour with John Cipollina from which the wonderful live album ‘Maximum Darkness’ emerged (again live at the Roundhouse). Was there any truth in the story that ‘Cip’ was on less than sparkling form and that his album parts had to be overdubbed by Micky Jones? AL: I think only one track. The problem he was having was that he played with a tremolo arm so much and it does bugger up the tuning of the guitar. We were in the studio listening to the recording and it was rocking along except for that one bit, which Micky touched up because he was able to imitate Cipollina perfectly. Micky was a fabulous guitarist who never played the same thing twice, I mean he and Deke were very different players and I loved the two of them together. But I’m pretty sure it was only the one track that had to be worked on and that this thing about guitar parts being re-recorded wholesale has become overblown.

What, then, prevented Help Yourself from achieving the same commercial success and cult status as stable mates Hawkwind and Man (they were no more transient in terms of personnel or chaotic, surely)? AL: They probably weren’t built for the road. I’m thinking particularly of Malcolm. Whereas the Man band was more or less designed to get in a van and travel and were hardy, Help Yourself were a bit more fragile. They found it hard work, and Malcolm suffered fits of depression which probably held them back. We tried to compensate by working around that to some extent, but they are probably more highly regarded by people now than they were at the time. Listening to that box set that came out makes you realise that they were really good and they were lovely people, and John Eichler who managed them was great. Malcolm in fact was at the book launch in May. Somebody told me he was there but I was in the middle of signing books and by the time I was able to go looking for him everyone had gone and so I didn’t see him unfortunately. Andrew put out and impressive, some might say foolhardy number of releases by splinter acts peeling away from the mothership for example Iceberg, Neutrons and Clive John out of Man and Robert Calvert’s solo LPs. This must have been commercially and reputationally risky even by the standards of the day. How did he manage to justify so many tangential projects and did nobody say ‘Andrew, Clive John for god’s sake! What are you thinking?!’ AL: Er, no, to be honest. Martin Davis was the managing director and he just let me get on with it. I’ve no idea what Clive John’s album sold, probably not a great deal, but there again I liked Clive and he’d been in the Man band so I thought ‘why not?’ It wasn’t expensive and the thing is I always had something successful on the go. Creedence Clearwater Revival helped because they were always having hits and The Groundhogs and Hawkwind were becoming successful which allowed me to indulge a little. I kind of got left alone by Martin who was very supportive, probably because I was right more often than I was wrong.

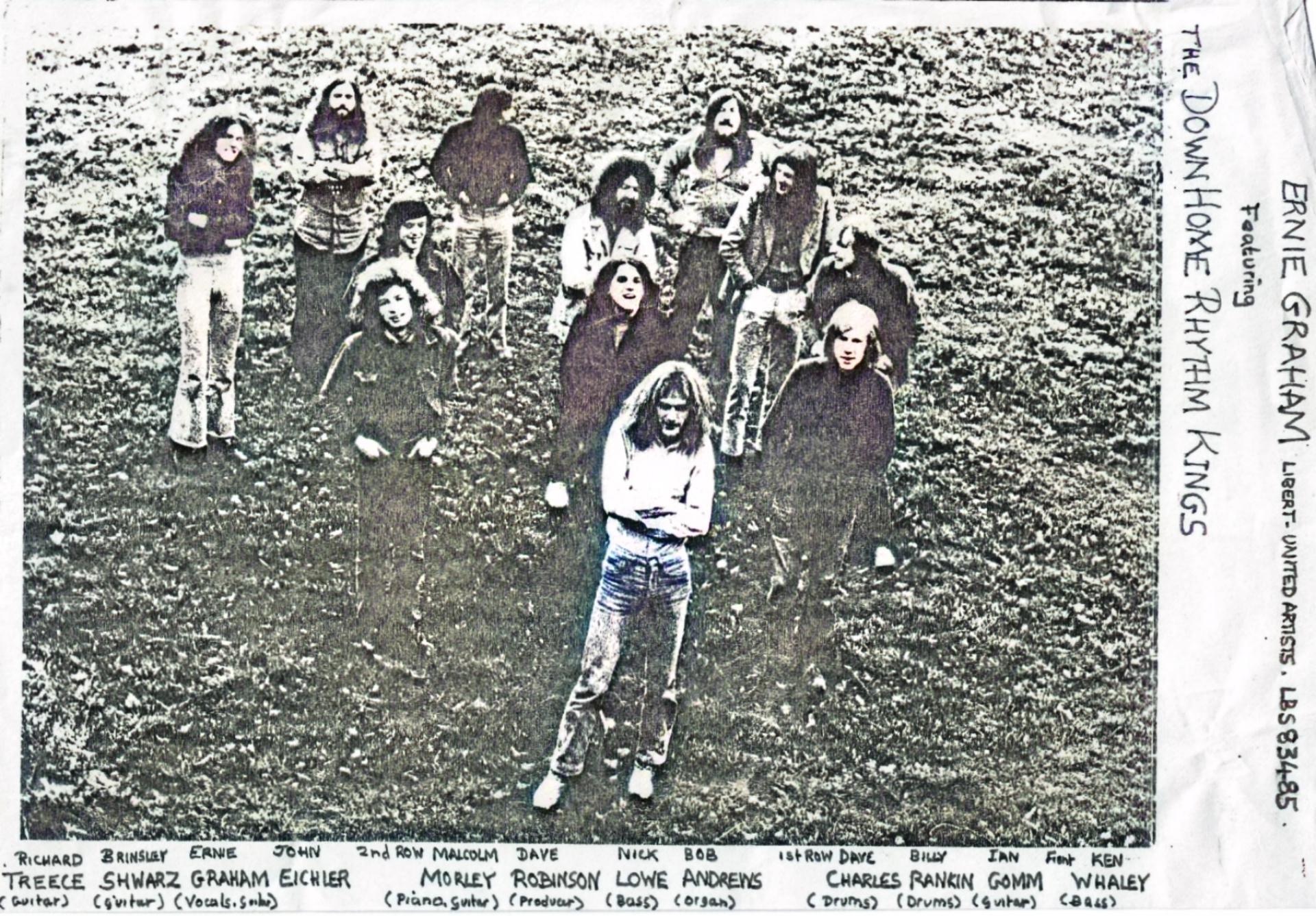

Photo:

the cast of the Ernie Graham solo album, featuring

members of Help Yourself and Brinsley Schwarz, plus

manager John Eichler (back row, right hand side). Hand

annotation by Richard Treece (back row, left hand

side) So was being given carte blanche simply a reflection of your impressive track record or a sign of more benevolent times? AL: Probably a bit of both, I would say. We weren’t spending huge amounts of money in the studio, especially in the early days. Take the first Hawkwind album. Other than ‘Hurry on Sundown’ and the b-side [‘Mirror of Illusion’] we did it all in one go in an afternoon and then Dick Taylor finished it off in a couple of days. It was only later when we would spend a bit more, maybe take a couple of weeks, and we’d use Rockfield where the rates weren’t particularly expensive and you’d come away with a finished record. With Man we probably didn’t spend much until later on either. But with bands like Hawkwind and Man they used to develop their material live so that by the time they went into studio they pretty much had it down as opposed to having to learn material during studio time, all of which helped. Given that the book mentions that Andrew lost much of his enthusiasm for Hawkwind after they dismissed Lemmy, did he regret that Motorhead slipped through the net? AL: Oh yes I do, yeah. That was definitely the one that got away. I was too quick off the mark in a way. I was talking to Lemmy about doing something and he said he wanted the nastiest, loudest rock ‘n roll band in the world. Lucas Fox from Warsaw PAKT came in on drums and I was really happy that [guitarist] Larry Wallis, whom I knew from Shagrat and Pink Fairies, was involved. That was the first Motorhead. Doug Smith was managing them and Dave Edmunds agreed to produce an album so it was all coming together. Doug got them a few support dates with Blue Oyster Cult, I think, and it was all stacking up nicely, and I got the artwork done, which was the beginning of the famous logo. They went to Rockfield and after the first week I thought I’d go down and see how things were going. Dave played me four tracks, which sounded great. But then he said ‘I can’t go on, I haven’t slept for a week’. He had gone a funny shade of green! Also, I found out later that he was being pressured by Swansong records, and particularly Peter Grant [Led Zeppelin’s legendary intimidating manager] to get his own album done. The next problem was that with a residential studio like Rockfield you’re stuck there. You can’t just hand studio time to someone else who needs it like say in London. Even allowing for the great relationship I had (and still have) with owner Kingsley Ward if you have studio time booked you have to pay for it. A friend of mine, Fritz Fryer, had been guitarist with the Four Pennies in the 1960s and his wife was cook at Rockfield. Fritz had recently started producing and so I prevailed upon him to finish off the album, which he did. But then there was pressure from Dave Brock on Doug Smith. Dave was leader of Hawkwind and he wasn’t happy about Doug managing a new group with Lemmy, who had recently been kicked out of Hawkwind. That put Doug in a difficult situation because at that time Hawkwind was where the money was coming from to pay the bills. Later Doug would solve the problem by getting my friend Wayne in so he could truthfully say that someone else was looking after Motorhead. However, in the meantime I had an album produced by different people, no manager and to cap it all Lemmy went and changed the group. Out were Larry and Lucas and in came Fast Eddie and Philthy Animal, which left me with a redundant album by a band that no longer existed. Lemmy was coming in every other day asking for money and I was thinking ‘I’m going to end up managing them as well as all the other stuff I have going on’. So I just let them go and I promised that as long as I was there I wouldn’t put the album out. Of course after I left the guys who came in after me released it. So yes I regret not making it work with Lemmy and I had to watch them get successful, initially through some good friends of mine, Ted and Roger at Chiswick, who released their Motorhead single and somehow stumped up the money to finish off the album featuring the current band. But yeah, I was in there too early with Motorhead. Speaking of getting in early, Andrew was an early champion of Kosmische or Krautrock , pre-empting a movement that has proved to have an enduring appeal and perhaps spotting something that others may have missed or simply not have been aware of. (AL): There were two very good guys in Germany. One was Siegfried Loch, who used to produce a lot of stuff for Star Club like The Searchers before they signed to Pye and who I’d known from various festivals. He employed a guy called Gerhard Augustin who became my opposite number in German Liberty, and we got on really well. We liked the same music and were interested in the same things. He’d signed Amon Duul II and finished off the first album - ‘Phallus Dei’- which he sent it to me. I thought ‘who the hell are these guys’? Anyway I agreed with Gerhard that they were interesting and so I put it out. It didn’t sell very many copies but it got a bit of mention in International Times and the underground press. At that point, just before ‘Yeti’, they said ‘we’ve found another group but we need you to be convinced about this otherwise they won’t sign’. That turned out to be Can. It was important to them not just to get a release in the UK but be promoted. Ultimately they wanted to get to America and the easiest way of doing that was via some success in the UK, rather than what happened in Germany. They’d pressed up some copies of their first album themselves on their own label. Those arrived via a very unlikely source, namely Abi Ofarim of ‘Cinderella Rockefella’ fame and who in the very early days had got involved in the group. He was in Martin’s office and I got this call to come down because Abi had this package and I thought ‘what the hell’s he doing here’. So he gave me a copy of the first album and Holger Czukay’s ‘Canaxis’ record. I thanked him very much, went off to a lunch appointment, came back later, put it on and was completely blown away. I thought ‘got we’ve got to do this’. So I was involved in the signing but strictly speaking didn’t set it up. But we agreed to work on it as though it was one of our groups. That’s how highly we thought of it. Neu was from a different source and that happened a bit later and purely because it appealed to me. That was from a label called Brain. Was Lauder surprised that, as well as lasting significance, its stock seems to have risen with the passing of time? (AL): Yeah, Can are practically godlike now. I thought it was really important at the time. I played it to Andy Dunkley the DJ who was a friend of mine and who worked at Simon Stables record shop in Portobello Road and he said ‘I’ve got a big festival this weekend you’ve got to lend it to me’ and I thought ‘hang on I haven’t even signed them yet’! So he loved it but not everybody got it, some found it too difficult so it was a bit ‘Marmite’ originally. But the people who loved it thought it was the best. Looking back I think the UA releases were the best, I never really cared for the Virgin stuff in the same way. On which subject did it ever irk that Richard Branson and Virgin Records are often credited with ‘breaking’ German bands in the UK even though UA was first to the pass? (AL): Erm, no, not particularly. I think that was to do with Faust [Virgin famously released Faust’s third album, ‘The Faust Tapes’, for the price of a single, resulting in healthy sales of 60,000 in the UK]. It didn’t really bother me, I knew those guys as well. With the likes of Hawkwind, Man and Groundhogs running out of road in the mid-70s, and Brinsley Schwarz never really taking off, was ‘pub rock’ and the Feelgoods seen as UA’s - and rock’s - future? (AL):

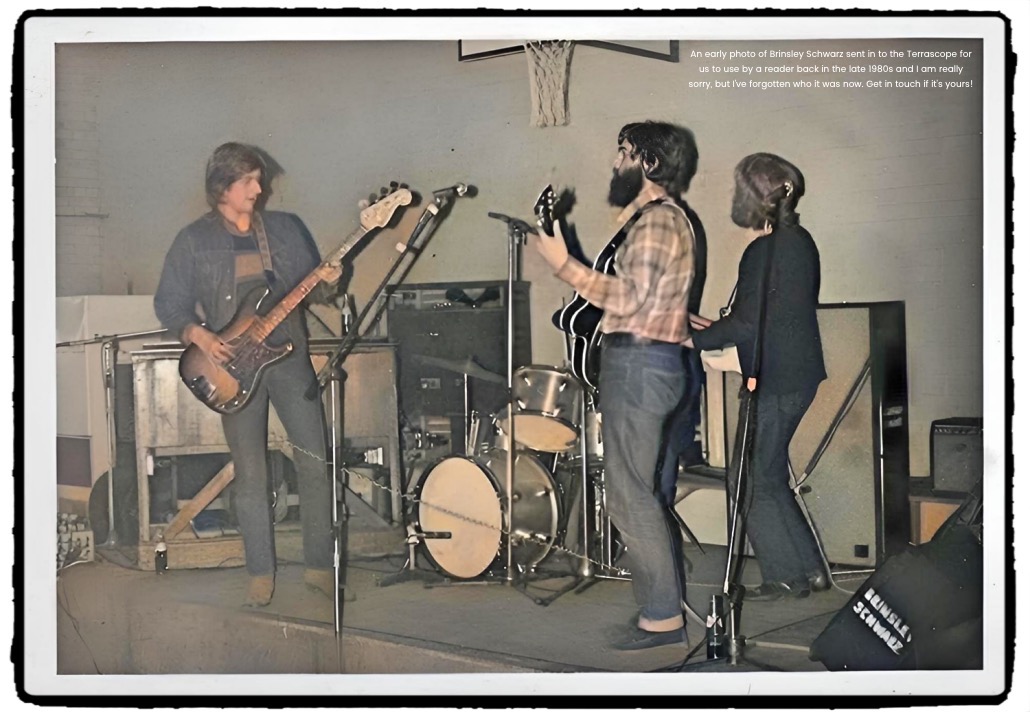

Brinsleys

probably did better than people imagine. They were big

in Holland for instance. Not that it

was a huge market, but when you totted up the album

sales it sort of validated making the next one. I was

convinced at some stage that Nick [Lowe] was going to

have a hit and I really loved the band, you know.

Those records still sound good because there were no

dated effects on them. It was a case of just setting

up and playing.

It was Nick who told me about Dr Feelgood. I was putting together my two ‘hobby’ albums of beat groups. EMI were going to give me two Pirates tracks which were pretty rare. They were on the single that didn’t really sell and Johnny Kidd wasn’t on it because he had a bad throat. Nick asked me what I was up to and I told him this and he said ‘funnily enough I saw a band called Dr Feelgood a couple of nights ago and they reminded me of Johnny Kidd and the Pirates’. Nick told me that he wasn’t going to say they were the next big thing but that they’d be right up my street. A couple of nights later I saw them play The Kensington and I completely fell for it even before I heard them play, just seeing these characters. They were brilliant. I was looking around the room worried that there might be other A and R guys there because I just had to sign them. It was exactly what was needed because things were getting a bit boring, what with Focus and ELP and all these groups I couldn’t stand, with mountains of keyboards and which felt a bit like going to a classical music concert. We’d lost the plot. The Feelgoods reminded me of what had got me hooked in the first place and what we needed to get back to. I just knew they were going to be successful. Bear in mind that we’d also helped to create that pub rock thing of which the Brinsleys had cottoned onto pretty quickly. We were getting fed up with paying tour support for bigger groups, playing to a half empty room and towards a PA and lights that we were only getting half use of. So we started this little agency called Iron Horse, me and Martyn Smith and we started booking bands into pubs. Pubs had always been important, but it was usually in the back room, not the actual bar where you could buy your pint and stand there and watch the band, like the Kensington and Tally-Ho. It became a conscious thing to book venues like that, and that scene led to the Feelgoods. United Artists struck gold with the ‘punk/not punk’ Stranglers and also Buzzcocks just as Andrew and Martin Davis were about to leave to help set up Radar Records at the end of 1977, and which would go on to have big success with Nick Lowe and Elvis Costello. Did he know that change was afoot? (AL): I certainly didn’t have an inkling that everything was going to change either when we signed The Stranglers or Buzzcocks. It was a few months afterwards that we got wind of conversations between the American branch and EMI about acquiring UA in America. Neither Martin Davis nor I wanted to work for a corporation after having had so much freedom. We’d done very well by breaking acts, which the likes of Warner Brothers weren’t doing. We always managed to have something happening, so that when the older bands came to an end the Feelgoods kicked in and as they got big then along came The Stranglers. And I’d keep myself busy putting out things like Mike Wilhelm records through Zig-Zag even though they weren’t going to sell. You couldn’t do that as part of a corporation. Surely UA offered inducements to try and get Lauder to stay? (AL): No, not at all! I had been offered loads of jobs over the years with CBS and on three occasions by Richard Branson at Virgin, but there was always something, like the Feelgoods, that I didn’t want to be separated from. I was enjoying it too much and had a good relationship with Martin Davis. It was unique. There wasn’t another label quite like it. We weren’t huge we were a sort of ‘mini-major’, not independent but working independently of the American company, the best of both worlds. I did get offered was the managing director of Arista at exactly that time that we struck the Radar deal, but the latter was too attractive given that all we really had to do was bring in four new acts a year and WEA would handle the marketing and all that. It was the right decision to leave when we did as we’d have been sucked into the parent company. In fact The Stranglers went around to UA’s office a short time later only to find out that it had been closed and to be told that they were part of EMI now. We did try and take the Buzzcocks with us because, unlike The Stranglers who were by then established, they were still finding their feet a bit and had turned down more money from CBS to sign with us because they wanted to go with the guy who’d signed Can [LAUGHS]. I felt a bit bad that we had to leave them behind. Aside from creeping corporatism what, fundamentally, changed in the industry between Andrew joining Liberty and hanging up his spurs? (AL): Lawyers became more and more involved! Some of them would push up the deal. We’d say to a band well what do you need? A van, a backline a couple of guitars and something to live on and we’d work out a deal based on what was needed. And it worked fine as you had sensible managers like Chris [Fenwick] who managed the Feelgoods and Dai [Davies] who handled Brinsley Schwarz and The Stranglers who knew what was needed and that became the advance. It didn’t feel right to be involved in competitive bidding with other labels. But then some lawyers started rowing themselves into the deal. You’d put in a reasonable first draft of the contract and it would come back covered in red ink and with pages ripped out and you knew as soon as certain names were mentioned as being involved that it was going to be a horror story. That’s how they’d justify their fee and it made it hard work. It became much more of a business as it grew. Between 1967 and 1977 in particular album sales went through the roof and it became big business and probably less fun as a result. To any A and R aspirant reading your book, what advice would Andrew hand down to them or does that world even exist anymore? (AL): God knows how you’d go about it now. I don’t even know nowadays whether I’d be attracted to it. There are more and more artists putting out their own records or working with micro-labels. It requires less and less leadership and involvement from big record companies. Is that a good or a bad thing? (AL): It may be a bit of a shame in one respect. If you’re starting out then unless you’ve a very clear blueprint of what you want to do and how you want to do it then you’d probably benefit from a bit of help from someone who can give some advice on matters of production or track running order. I mean it’s their record after all and if they want to go their own way so be it but having that sort of constructive relationship is useful, I think. Time has a way of thinning out the old address book and sadly the number of ‘absent friends’ is mounting (we’ve lost main Groundhog Tony McPhee, Tony Hill of High Tide and Hawkwind’s Nik Turner within the last year, as well as Helps manager and Hope & Anchor landlord John Eichler). Did Lauder keep in touch with anyone from those days at United Artists and who get a mention in the book? (AL): Yes, I kept in contact with pretty much everybody who was still around! I mentioned Doug [Smith] earlier, Martin Davis of course and Dai Davies. I’d seen Tony McPhee a few times during my time at Silvertone through my association there with John Lee Hooker. I’d first met John Lee through Tony. It was going to see John Lee back in the 60s at the Flamingo that I realised how good Tony was and I really wanted to do something with him. So I saw him quite often over the years. Nik Turner I probably spoke to most out of the Hawkwind guys, apart from Lemmy. I’m still in touch with Ken [Pustelnik] from the Groundhogs. As regards Brinsley Schwarz, I saw Nick [Lowe] in May when he came to the book launch - in fact we’ve had a long standing working relationship - and I’m still in contact with Ian Gomm and Bob Andrews. Lucas Fox is living in Paris and is putting together a book about the early days of Motorhead, which was an eventful time! We speak every couple of weeks or so. Irmin Schmidt from Can lives in France and we speak now and again. I’m in touch with Sparko [John Sparkes, Dr Feelgood bassist] still and until recently of course with Wilko [Johnson].The Man guys I stayed friendly with for a long time although there aren’t many of them left, now. I was particularly close to Deke, who used to spend a lot more time in London than the others and was very close to John Eichler the manager of Help Yourself, who went on to run the Hope and Anchor. Jean-Jacques Brunel from the Stranglers is one of my best friends. In fact I saw him last Saturday. The Stranglers played a free concert in another village near me and where he lives. In fact the whole thing has a unique family atmosphere even to the extent that Jean-Jacques’ landlord when the Stranglers were starting out was Wilko!

(AL): In the early days I probably put too many records out as a result of which some things, like Gypsy, got a bit lost. Same with Reg King from The Action and Cochise, who were another one that got away. They were another Clearwater act and who had trouble holding down a stable line-up. I was reminded of them only yesterday as I was signing a copy of the book for BJ Cole who was in the band. BJ is in fact very friendly with JJ from the Stranglers. I wasn’t even aware they knew each other, but it seems they met in my office at UA! Small world and it’s nice that relationships have continued from those days.

Anyway, later on we got better at concentrating on particular acts to ensure they fulfilled potential, like the Feelgoods and The Stranglers. In

retrospect

I think I’d have used better quality card like Island

did for their sleeves and which was much more

expensive but held their colour better. I did learn to

stick my oar in with the artwork and advertising,

though. Too often in record companies you’d get this

hand-off between A and R and marketing which resulted

in some god awful sleeve or promotional materia The Lauder approach to the roster comes across in the book as one of supportiveness and of indulgence of his charges. (AL): I think it helped a lot that I was able to put out records that I wanted to by people that I liked and the same with their management. It was my deliberate policy to work with people with whom I felt comfortable. I thought, well, I’m going to be spending a lot of time with these people and I don’t want to be constantly living in dread of the phone ringing. So that stopped me from working with certain acts. I never had that trouble with the likes of Man who were all great characters and very funny. Help Yourself and the Feelgoods the same. Their managers were pretty much part of the band and cared about them. Even The Groundhogs, until the Mafia took over! I wasn’t happy how that ended. Looking back it was the beginning of the end I suppose. The things you thought would be successful but they weren’t, that was probably due to my heart not being in it which meant I subconsciously didn’t go the extra mile. But overall it helped that the people working for the company got on well. There was no competition or resentment of each other’s involvement. It just happened fortuitously that way. We’re all meant to love our children equally but if Andrew were to leave everything to just one of his Liberty/UA charges who would it be and why? (AL): Oh boy, that’s a difficult one! I still love so many, the Brinsleys, Man, Helps and Feelgoods...I’m great friends with JJ from The Stranglers. I couldn’t really say, I have such great memories and fondness for these and indeed others like Hawkwind, The Groundhogs, the list goes on. So no, I can’t pick just one.

Andrew Lauder, a gentleman, a true inspiration and the founder of a legacy for which he is the deserving recipient of Terrascope’s undying gratitude. In any just society he would be awarded a blue plaque and within his lifetime. What it would say is anyone’s guess, but something along the lines of ‘Andrew Lauder worked, lived and loved life here [dates]. It was fun and I got lucky!’ might do it. Make it a big one, then.

‘Happy Trails - Andrew Lauder’s Charmed Life and High Times in the Record Business’ by Andrew Lauder and Mick Houghton and published by White Rabbit is currently available now in hard back White Rabbit Books Ian

Fraser

Layout

& image archives: Phil McMullen, (c) Terrascope

Online, 4/24 |

ord

labels whose output played a pivotal and lasting role in

our musical education. For many of a certain age, one

such label was United Artists (UA), one of the best,

most authentic UK semi-independent imprints of the early

and mid 1970s and which nurtured many of the acts that

underpin the ethos of Ptolemaic Terrascope. Indeed

without certain key releases by UA it may be that

Terrascope would not have happened in the first place.

ord

labels whose output played a pivotal and lasting role in

our musical education. For many of a certain age, one

such label was United Artists (UA), one of the best,

most authentic UK semi-independent imprints of the early

and mid 1970s and which nurtured many of the acts that

underpin the ethos of Ptolemaic Terrascope. Indeed

without certain key releases by UA it may be that

Terrascope would not have happened in the first place.