|

Long before Tory politicians, film stars and TV celebrities began to colonise it, long before comedians like Harry Enfield ridiculed it, and long before the property developers came in and completely transformed it, Ladbroke Grove in West London was home to a vibrant colony of artists, musicians, Bohemians, drug dealers and misfits – an enclave that back in the late 60s and early 70s that could hold its head up as England’s answer to New York’s Greenwich Village or San Francisco’s Haight Asbury. It was a special area – Eric Clapton formed Cream whilst living there, Jimi Hendrix died there, and Van Morrison sang about it on the song ‘Slim Slow Slider’ on his Astral Weeks album. Writers such as Michael Moorcock, J G Ballard and Colin MacInnes all drew inspiration from and wrote about the area, and Nic Roeg and Donald Cammell immortalised it in their 1968 cult film, Performance.

We’re talking about Notting Hill and the area to the north of Holland Park Road that stretches up as far as the Harrow Road and Kensal New Town, Westbourne Park and Bayswater to the east and North Kensington and Holland Park to the West – an area that straddles the W10 and W11 postal districts - specifically the territory that lies in between Notting Dale and Notting Hill Gate criss-crossed by thoroughfares such as Portobello Road, the Westway and Ladbroke Grove - and it is the latter street that has come to lend its name to the whole area.

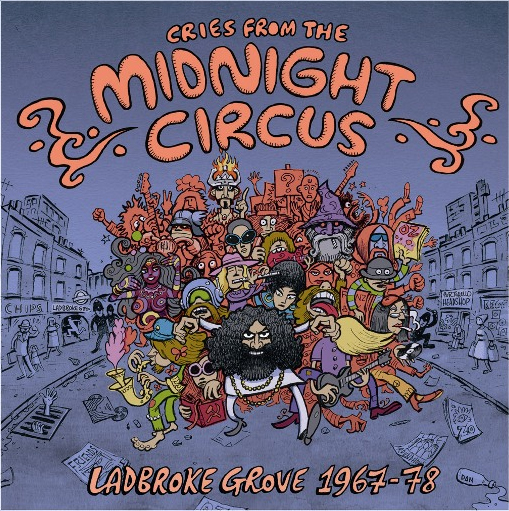

40 years ago the Grove was the epicentre of the British Underground. The point of the compilation is not to talk about the bands featured per se but to look at them in the context of the 60s cultural revolution and more specifically to see how they interacted with the Underground and Ladbroke Grove in particular. Some were in the very eye of the hurricane sweeping the country back then, agents of change on a mission to make the world a better place. And those that were not at least paid lip service to and played role in the rich musical backdrop to what was going on around them.

The Counter Culture Arrives

Post-World War II West London saw a growing West Indian Community take root – it was full of cheap housing with many properties owned by notorious slum landlord Peter Rachmann – and in the late 50s it saw the arrival of the first manifestation of teenage rebellion in the shape of the Teddy boy. It was there in 1958 that the riots happened (‘called so by the press’, says Michael Moorcock, ‘but not much of anything really’) and the final stand of British fascist Oswald Mosley who only got around 120 votes in the end. The scene is vividly captured in Colin MacInnes’ Absolute Beginners in which he describes Notting Hill as Little Napoli.

There’s no single factor to explain why the Grove came to be the focus of the anti-war, anti-establishment, psychedelic, culture rebellion of the hippies in the 1960s and 70s with its squats and crash pads. Mick Farren, who lived there in '64 just after the Profumo scandal, says, ‘One Word – Students.. From Lancaster Gate heading west was the nearest slum bedsit land to all the colleges in the West End – London University, St Martin’s, RADA, Central etc…of course the further west you went, the more you got into trouble’. Michael Moorcock had lived around the area since the late 50s and as he says, ‘Ladbroke Grove was pretty much an exact equivalent of Haight Ashbury and for fairly similar reasons – I of course lived there before the phenomenon and saw it all grow up around us. Anyone reading about Notting Hill in the very early 60s or before will find a very different world mostly of gang battles and so on. And yes we moved there as everyone did originally because it was cheap and considered dangerous (while being only a 20-minute walk from the West End).

Following the Wholly Communion poets’ conference at the Albert Hall in 1965 featuring father figure Beat writers like Allen Ginsberg and Lawrence Ferlinghetti, the UK counter culture began in earnest – the London Free School was a kind of community action group based at 26 Powis Terrace – a disparate band of activists and local figures such as Michael X, John ‘Hoppy’ Hopkins, Joe Boyd, Jeff Nuttall, Brian Epstein, R D Laing and Peter Jenner who described it as the first ‘public manifestation of the Underground in Britain’. Hopkins elaborated that it was ‘an idea – it lasted a few months and so many interesting things came out of it’ including the first two Notting Hill Carnivals – which as Michael Moorcock points out, ‘was an attempt to give the area a certain respectability and was based on the Soho Festival i.e. it wasn’t considered a predominantly black festival’.

It was out of this initiative that in 1966 the first signs of psychedelic rock began to manifest in this part of London – Peter Jenner had stepped away from his role of lecturer at the LSE to become a pop group manager and had become involved with band he’d seen at the Marquee, the Pink Floyd Sound– they were a perfect choice for the festivities around the first Carnival and duly did a show at All Saints Hall playing their weird brand of rhythm’n’blues and electronic noises whilst a crude lightshow of projected coloured slides was the backdrop. Within months the band had become the darlings of the emerging Underground playing the International Times launch at the Roundhouse in October and the rest as they say is history

The New Breed

1966 rang in the changes – in the wake of the Floyd came bands like Tomorrow, Arthur Brown and California’s Misunderstood all of whom feature on this album. [the Misunderstood in fact didn't make the final cut - Phil.] Indeed first place the Misunderstood headed for when they arrived in London was Notting Hill and the mews flat of their mentor DJ John Peel’s mum in Jameson Street W8.

There’d always been drugs around the music scene but rock musicians were amongst the first to experiment with a new psychedelic drug called LSD which along with pot became the Underground’s preferred stimulants – it was an era of experimentation first rather than recreation. And these bands were at its forefront. Over the winter of 66/67 the Underground in London mushroomed with clubs like UFO opening and events like the 14 Hour Technicolor Dream in April heralding the Summer of Love.

Mod heroes the Action were one of the first outfits to be seized by the spirit of the times, changing the direction of their music away from Tamla and soul towards the West Coast sound. The band finally called it quits in Chelsea’s Lots Rd and as they began to embark on their new route as Mighty Baby the various members moved into the Grove – ‘it wasn’t a conscious thing to move there’, recalls bass player Mike Evans, ‘we weren’t into it in a territorial way. Bam [King] and I lived in Tavistock Road for a while. Ian [Whiteman] off St Luke’s Mews off Westbourne Park Road and Martin [Stone] lived in Westbourne Park Road just past Portobello Road…our roadie Mouse’s mum had this house in Tavistock Road – she was one of the instigators of the Carnival and helped start the Notting Hill Housing Association. I remember playing All Saints Hall with Alexis Korner and the Third Ear Band – it was Legalise Cannabis benefit – the place was surrounded by police – you didn’t know when they were going to come in and in the end they didn’t. Mighty Baby with guitarist Martin Stone as their ideological leader would eventually follow a path that took them by the 70s deeply into Sufism with most of the band joining the Dervish order.

The Edgar Broughton Band would soon be clutched to the bosom of the revolution – their brand of political heavy blues rock inspired by Frank Zappa and Captain Beefheart would quickly turn them into popular counter culture figures. Having signed to EMI in early 1969 the original trio moved down to London from their home town of Warwick and was initially based in the Grove. Says leader Rob 'Edgar' Broughton:

‘When we first moved to London we lived in Colville Terrace not far from All Saints Hall…we jammed at the Thursday sessions at All Saints Hall. I remember the Floyd were there once. Syd turned up and played my Strat. Oddly that Strat was played by Syd, Peter Green and Eric Clapton at various times. Good eh? The Grove was full of lovely hippie girls and boys and acid derelicts who were amusing to dangerous. It had its drawbacks back then although most people seem to think it was a perfect decade. Wrong! We were friendly with the Deviants and the Pink Fairies at the time but only socialised with them on tour as did most of us’

Quintessence was a band very much born out of the Grove, celebrating their home in the song ‘Notting Hill Gate’ featured here - a sextet who based their music on ragas and mantras and took their Eastern path very seriously. If bands like Quintessence and Mighty Baby put spiritualism at the heart of their music, the Deviants and their successors the Pink Fairies reflected the more radical, some might say realistic side of counter culture – their story has been told many times and I refer you to the bibliography below – but these bands together with various other figures such as Steve Took from Tyrannosaurus Rex and the Pretty Things were to play a dominant role in the Underground – the Pretties had been one of the few old guard to successfully make the transition into the psychedelic era – always rebels the Pretty Things cut a stylish and influential swathe through this whole period releasing two of the most redolently psychedelic 45s of the time of which ‘Defecting Grey’ is represented here before going on to cut two of the era’s greatest LPs, S F Sorrow and Parachute.

These bands worked out of the Bryan Morrison Agency and inevitably did gigs together which would often descend into cacophonous jams with Deviants singer Mick Farren leading various combinations including Twink former Tomorrow and some time Pretties drummer through covers like the Byrds ‘Why’ or the Velvets ‘Sister Ray’ – as the scene’s arch pranksters they would turn up at muso drinking haunts like the Speakeasy as the Pink Fairies All Star Rock’n’roll Motorcycle Club. To cut along story short this aggregation under the leadership of the extremely well organised Farren cut two LPs at the close of the 60s that have come to epitomise the British Underground – Twink’s Think Pink and Farren’s Mona: A Carnivorous Circus, from which this compilation boasts ‘Then Thousand Words In A Cardboard Box’ and ‘Mona’ respectively. It was as if these guys could see into the mirror darkly and what was coming– if bands like Quintessence were the positive spiritual yin of the scene then were the yang. Think Pink was the more upbeat more utopian record, Mona in contrast was a more deeply disturbing beast – a collision of too much acid, the Hells Angels and the Marquis de Sade done to a Bo Diddley beat!

Another band that embraced the positive idealism and potential of the era were Juniors Eyes led by Mick Wayne who’d come out of the early 60s Surrey r’n’b scene – after his band the Tickle split Wayne began hanging around Peter Jenner’s Blackhill offices looking for a band – hooking up with Donovan sideman Candy Carr and bassist Honk, they moved into the top two floors of an old Victorian shop parade in nearby Holland Park (the setting later for the Pink Fairies infamous ‘Uncle Harry’ song) – Wayne would eventually expand the group with singer Grom and guitarist Tim Renwick – ‘we were the archetypal underground band’, Mick told me in 1991. Their only album Battersea Power Station from which ‘So Embarrassed’ is included here was ‘to do with numerology, to do with Tibetan Book of the Dead. It was to do with layers of conscience and consciousness starting with total war and with total peace’. Talking about the band at the time and success he added, ‘It really means finding the point of communication between yourselves and you audience and playing on it. Feeling a surge and good vibrations is the sort of commercial success I’m interested in’.

Sadly Juniors Eyes had to fold when Mick Wayne was told that in order to cure his back problems he should take a complete rest that included not sitting for hours in group vans – in early 1970 guitarist Tim Renwick and bassist Honk found themselves in a house at the end of St Helen’s Gardens (no longer there) - it was split into bed-sits and living in the one next door was Cal Bachelor fresh from the break up of the Village – the three got together to form Quiver. As Tim recalls ‘Cal and I had a copy of the first Poco LP, nobody was playing music like that in England at the time’ Playing a brand of warm country rock that should have turned them into the Grove’s version of the Byrds, Tim says, ‘we were very much a people’s band when we started out, the first 6 months we played for petrol money, doing a lot of local stuff – we were very happy to be in the mould of a people’s band especially when we played places like the Roundhouse which seemed a natural home for us, and we used to see a lot of the local bands like Hawkwind, Quintessence, Mighty Baby and the Pink Fairies’.

Honk sadly turned out to be unreliable – ‘he was doing lots of drugs’, says Tim, ‘hanging out with people like Paul Kossof and doing lots of pills’. His replacement ‘keen as mustard to get involved’ was Bruce Thomas another refugee from the Village – a virtuoso super trio – described as ‘an impossible melting pot of Albert King, Holst, Jimmy Smith and Richie Havens’ put together in the Grove by former Them keyboard player, the late Peter Bardens: ‘All three of us were on different drugs’, Bardens later confided, ‘a thousand dramas culminating in a getting-it- together period in a country cottage, which turned into nothing more than a vast acid loon. It had obviously reached a point of no return’. In the aftermath he signed a solo deal with Transatlantic recording two LPs including The Answer from which ‘Long Ago Far Away’, so wistfully sums up this period.

The Revolution on Wax

The phenomenon of the counter culture caught the record industry with its pants down. As Mick Farren said back in the day, ‘I was talking to the chief A&R man of one of the big corporations and he was really under the impression that the Mothers and the Doors albums were just novelty records. He fondly believes that there are only about 8 hippies, they all live in Notting Hill unwashed and ragged and never buy any records’. By 1969 there was a scrabble to exploit the emerging long hair audiences and the changing tastes of the new generation.

It’s always been a mystery as to why – given the fierce alternative spirit of the hippie age - that there wasn’t an explosion of independent record labels in the same way as there was 10 years later with the advent of punk rock. Manager Doug Smith suggests, ‘it came down to money, who would pay the studio bills and stuff, and the big labels had the connections to America – most musicians are self serving and wanted to be rich and famous – All Saints Hall was fine but you made no money and you’d ask yourself why you’d played it’ There were a handful of small labels during this period that were started in true hippie style – the Underground Impresarios label which released the first Deviants LP, Ptoof, from which the primitive garage rocker, ‘I’m Coming Home’ is featured on this compilation, DJ and record shop owner Simon Stable’s eponymous label which was based in Portobello and released the second Deviants album, Disposable and Sam Gopal’s Escalator from which ‘Midsummer Night’s Dream’ is also featured here. Taking its name from the hippie venue over in Covent Garden, Middle Earth Records was another short lived venture in 1969. And influential DJ John Peel started his own company Dandelion that summer – hugely idealistic and non-commercial Dandelion relied on a series of corporate parent companies to finance it and when there was little commercial return first CBS, then Warners and finally Polydor pulled the plug on the label.

In 1972 Revelation Enterprises became another West London co-operative born out of hippie frustration with the system, sadly only releasing the magnificently complicated Glastonbury Fayre triple set (more than just a soundtrack to the second edition of the festival of the same name and whilst featuring many of the Grove bands, was as memorable for the stunning artwork and inserts by Barney Bubbles) - and the debut waxing by Chilli Willi & the Red Hot Peppers which featured ex-Mighty Baby guitarist Martin Stone. Indeed Richard Branson, in the wake of the success of his hip record stores including the flagship shop in Notting Hill would set up the Virgin Records label on Portobello Road in 1973 and exploit the alternative scene even if most of his signings were not culled directly from the local community.

In the main the majors remained in charge – EMI launched its Harvest label in June 1969 and amongst its first releases were records by many counter culture heroes such the Pink Floyd, Roy Harper, the Third Ear Band, and by the Edgar Broughton Band, and the Pretty Things, both of whom have contributions on this compilation. For underground foot soldier Mick Farren there was much irony in this as he opined at the time ‘..Harvest is just a joke. Some of their product is good but there’s still a big credibility gap between them and the consumer. It’s not all friendly and Stonehenge with the sun coming up, it’s Manchester Square and it’s raining’ – a reference to Harvest’s marketing campaign and its HQ in the West End.

Yet Farren himself got caught up in a similar if less cynical transformation when folk label Transatlantic decided it had to go hippie and sign some rock bands – heralded as ‘where the electric children play’, the label signed the Deviants from whose third LP ‘Billy the Monster’ is included here, Jody Grind, Peter Bardens and later West London outfit Stray all of whom have tracks featured here.

Chris Blackwell had set up Island Records located in Basing Street in the Grove in the early 60s to promote the sounds of his beloved home of Jamaica but by 1967 he was also signing white British acts such as Traffic one of the first true counter culture bands and by 1969 had a formidable roster including Quintessence from whose debut LP In Blissful Company ‘Giants’ was the opening cut. And over in the West End Liberty Records later taken over by UA were fortunate to have an incredibly perceptive, incredibly young and energetic A&R man who was to play a significant role in helping many of the Grove’s bands – Andrew Lauder who signed High Tide, Cochise, Hawkwind, and later Michael Moorcock’s Deep Fix and Motorhead all featured here. Andrew worked closely with a company whose name was to become synonymous with the Grove and the Underground and alternative English rock of the time.

Clearwater Productions

Like Lemmy and Sandy's (from the Fairies), Doug Smith's father was in the RAF. Doug moved to the Notting Hill area in the early 60s and he was initially involved ‘in a band with friends I’d grown up and they were called the King Bees’. He’d then turned his hand to interior design but had gone back into management with a group called England’s Home and Glory which didn’t last long. Then in 1968 he was accosted one day in Notting Hill by guitarist David Costa who asked him to manage his folk rock band Trees. By this time he was living in Westmoreland Mews behind Westbourne Park Road at the bottom of Great Western Road. He met Richard Thomas who’d been the social sec at Canterbury Uni and was involved with a band called Skin Alley, an eclectic quartet whose music had overtones of jazz, classical and folk – who recorded for both CBS and later for Transatlantic (a track from their Two Quid Deal LP is included here) - and through a Dutchman Rick van Henkel he met Wayne Bardell.

The three decided to work together as Clearwater Productions out of Westmoreland Mews and quickly established themselves as the music promoters par excellence in the Grove using All Saints Hall and some times Porchester Hall (where Wayne remembers an especially brilliant gig by Hawkwind and High Tide) as venues. If Blackhill’s Jenner and King were self-styled ‘dukes of the underground’, then Doug and Wayne were according to Gong keyboardist Tim Blake, its Riccotti Brothers! There was no rivalry between the two companies though as Doug recalls, ‘we felt they were way ahead of us – we were definitely the Del boys of the scene - they had the organisational skills’.

Easter 1970 saw the combined forces of both companies descend on a pop festival at Le Bourget airport in Paris – ‘organisation was non-existent’, says Doug and it was raining. ‘None of the bands (including Daddy Longlegs, Trees, Formerly Fat Harry, Edgar Broughton, Ginger Baker’s Airforce and High Tide) would play but I convinced Hawkwind to go on and they were fantastic. They saved the Festival’. It was a wild weekend with Daddy Longlegs leading congas around the lounge of the hotel until the management learnt that Radio Luxemburg who were one of the sponsors weren’t going to pay the bill and the bands got out as quickly as they could’..

Using grass root tactics such as advertising in the underground press notably in ZigZag Clearwater built quite profile for itself. At various times its roster included the likes of Mick Softley, Bubastis, country rockers Cochise and Heron as well as the aforementioned bands. However by 1971 the company stalled, Doug was sacked by the others and it soon folded, though ZigZag founder Pete Frame has good memories of them, ‘They owed, I think, £50 for some full page adverts – and they knew we were operating on a shoestring thinner than their own. I had given up on ever seeing any money, but then out of the blue, a cheque arrived. I thought that was a very honourable gesture – and I’ve always maintained the greatest respect for Doug, Wayne and Richard as a result. It was an example of the hippie spirit. Pity there isn’t more of it about today’.

However you can’t keep good dogs down and Doug would soon return to the fray as Hawkwind’s manager guiding them through their greatest period of success whilst Wayne would be responsible for getting Quiver & the Sutherland Brothers together and their subsequent ride to fame.

Groovin’ in the Grove

By the early 70s the area particularly along its Portobello Road backbone was buzzing – a real hip community – the Electric Cinema had opened – Friends newspaper (later just Frendz) was based at no 307 above the clothes market of the same name, BIT the information and advisory service for the Underground run on a voluntary basis boasted ‘no bureaucracy, no files’ and there were a variety of hang outs and eateries such as Ceres whole food store, reflecting the prevalent taste for vegetarian organic food even back then – though many musicians favoured the more traditional nosh of the Mountain Grill (later immortalised by Hawkwind in the title of their fifth album), about which Doug Smith quips ‘the place was swimming in grease’.

Mick Farren reckons, ‘The pubs of freak significance back in the day were -from Ladbroke Grove tube station heading south - as follows...

The Kensington Park Hotel (KPH) Ladbroke Grove and Lancaster Rd. -- Full of junkies, long-haired lowlife, and Irish geezers too fucked up for the IRA

The Elgin -- Only a few points better than the KPH, but then they started having bands in the seventies and that's where the 101ers and London SS got started.

There was a serious Rasta pub on Portobello and Lancaster Rd which you only went if desperate to score (probably Oxo). Can't recall the name.

The Apollo on All Saints was a serious lefty pub, Claimants Union, Socialist Workers Party etc, plus rudies from the Mangrove. Never felt too welcome there.

Finches (Portobello Road) A regular haunt of most of us but it had its fair share of assholes, drugs squad, and tourists looking the hippies. Sometimes had music. There was this really obnoxious blind accordion player, but Paul Rudolph and Trevor Burton did play in there. Always seemed to be a lot of coppers hovering. Maybe the landlord didn't pay off.

Henneky's (Portobello) Had a garden and was a major hangout. Liked it better than Finches, but still the regular coppers, and tourists,

The Princess Alexandra (Portobello). The bullshit level in Henneky's, by about 1972 or so, caused Edward Barker and Roger Hutchinson to walk diagonally across the street and check out a pub that no one used except a few dodgy used car dealers. But there was a pool table. It was called the Princes Alexandra -- The Alex.. Boss, Lemmy, George Butler and I followed. Then Crazy Charlie and Hells Angels also adopted it. Bit by bit we made it our own and it stayed that way until it got too well known and full of Swedish Hawkwind fans hoping to spot Lemmy or Nic Turner. Ultimately it would be bought out, tarted up and become The Gold

The area was positively heaving with musicians – as Michael Moorcock recalled, ‘Ladbroke Grove was and is still is crammed with rock’n’roll people and it was almost impossible not to know at least half-a-dozen musicians who were either already famous or would soon become famous in the atmosphere, with Island’s amazing studios 10 minutes walk from my house and almost everyone you knew working in some capacity for the music business, it felt a little weird if you didn’t have a record contract’

Some bands had

gravitated there such as Steamhammer

Talking in 1970 Raja Ram flautist with Quintessence was more upbeat his chosen locale: ’if you live here, you meet so many people – poets, painters, all sorts – and I’d say it’s the most creative part of England - in fact one of the most creative parts of the world. I’ve lived in many of the world’s principal cities from Greenwich Village to Melbourne, but I’d say this place has really got the most zap going. Everybody goes round to everyone else’s pad to jam and talk and so on…there are an amazing number of groups in the Grove or who got their start in the Grove…I mean you go down Portobello Road on a Saturday afternoon and it takes you about 5 hours to say ‘hello’ and 1 hour to do the shopping!’

Figures as diverse as guitarist Davy Graham and some time Pink Floyd alumnus Ron Geesin lived there – also the late jazz singer and writer George Melly who lived in St Lawrence Terrace. After the Deviants fell apart in Vancouver, Mick Farren settled in 56 Chesterton Road, North Kensington and resumed business as usual writing, planning Phun City and instigating the White Panther Party whilst his erstwhile cohorts, Russ, Sandy and Paul re-organised themselves with Twink in a more cohesive musical Pink Fairies the B-side of whose debut 45, ‘Do It’ a White Panther-style anthem is included here.

After his sacking from Tyrannosaurus Rex and the debacle of the first line up of the Pink Fairies Steve Took settled into 100 Cambridge Gardens– during the next decade Took would typify the perspective of Grove folk as stumbling permanently stoned long hairs and it’s shame that Steve’s predilection for drugs got in the way of his musical progress as he wrote some fine songs for series of different bands he put together including Shagrat with future Pink Fairy and Motorhead guitarist to be Larry Wallis, and various other line-ups that included at various points Sandy and Russ from the Fairies, Mick Wayne from Juniors Eyes and Ade Shaw of Magic Muscle and Hawkwind fame.

Took was one of a number of Grove characters sadly not include here whose contributions made the place so unique – Michael Cousins aka Magic Michael was another – he was the embodiment of the hippie ideal as his appearance in Peter Neal’s documentary of the 1971 Glastonbury Fayre attested – espousing his revolutionary plan to build a new Jerusalem based on peace, love, long hair and beads –he would later try out as the lead singer of German band, Can and make a swan song 45 with members of the Damned.

Singer Carol Grimes formed Uncle Dog in 1971 whilst living at 8a All saints Road, next door to the Mangrove Café – Uncle Dog was a fine outfit, possibly the Grove’s answer to Big Brother & the Holding Company and their sole LP Old Hat didn’t entirely do them justice but the group in just 18 months saw a stream of the Grove’s finest talent in and out of its ranks including Honk, ex-Fairy, Paul Rudolph, ex- Mighty Baby lead guitarist Martin Stone, slide guitarist Sammy Mitchell and pianist Dave Skinner – another Grove veteran who would join another band in the area Clancy featuring Ernie Graham. One of their many drummers was George Butler another figure from the community who deserves a book writing on him having played with Eggs Over Easy, Formerly Fat Harry and would go on to play with the Lightning Raiders and later versions of the Deviants and Pink Fairies.

The British Underground never produced a wealth of graphic designers, cartoonists and painters in the same way that the USA did – there just wasn’t the equivalent of the Zap! Comics brigade who exploded out of the Haight in 67/68 – Robert Crumb, Gilbert Shelton, Rick Griffin, Victor Moscoso, Robert Williams et al though London could certainly match San Francisco’s psychedelic poster artists with its own Nigel Waymouth, Mike McInnery and Martin Sharp.

The underground had a handful of very special cartoonists such Hunt Emerson and later Bryan Talbot and best of all the late Edward Barker – described as ‘the wittiest and most idiosyncratic cartoonist to emerge from the British underground press’. A graduate of Moseley School of art Barker headed south where he was soon involved in IT and very much a part of the Pink fairies gang contributing to many to the band’s album sleeves – he also created a wonderful series of British comic like Nasty Tales and Heave.

But if there was ever anyone synonymous with the Grove it was artist Colin Futcher aka Barney Bubbles – legend had it that he had worked for a while with San Francisco’s great psychedelic poster artist Stanley Mouse but by the late 60s he was installed in a tiny one room studio, Teenburger at 307 Portobello Road where he contributed to Frendz as art editor – but it was to be as the designer responsible for most of Hawkwind’s albums that he would begin to earn his reputation.

X In Search of Space was many people’s first introduction to Barney’s prodigious talents with emblematic design that opened out to reveal a poster layout inside, it also included the Hawklog booklet designed by Barney, purporting to logbook of the crew of the Hawkwind spacecraft. Barney’s name would be linked with that of Hawkwind’s for most of the 70s designing all their famous sleeves including the intricate Space Ritual record, their stage sets, posters and other publicity materials. He’d also do stuff for other bands including the incredibly beautiful sleeve for the second Quiver LP and Michael Moorcock’s Deep Fix record. As co-founder Nik Turner says, ‘he had a profound influence on the band’.

For Free

Peter Jenner and Andrew King, the Pink Floyd’s first managers had set up Blackhill Enterprises in nearby Bayswater and in 1968 taking their cue from similar events in San Francisco’s Golden Gate started up the free Hyde Park concerts – bands like the Action, Edgar Broughton Band and Juniors Eyes played these first ones,

Although London itself hosted no major free festivals many of the Grove bands provided the lion’s share of the music at the key free fests of the early 70s, firstly at Phun City on Worthing Common in summer 1970 that boasted everyone from William Burroughs to the MC5, Glastonbury Fayre in 71 and Trentishoe in Devon in 73. The Richmond Free Festivals and many more followed in their wake.

As the 70s progressed one outfit emerged from the Grove dedicated to keeping the music free – this organisation was the Greasy Truckers led by John Trux who worked out of 293 Portobello Road – known to music collectors for two double albums released to benefit the organisation – the double Greasy Truckers Party recorded at the Roundhouse which featured Grove favourites Magic Michael, Hawkwind, Man and Brinsley Schwarz who’d been involved with Portobello-based company Famepushers and a year later a second volume recorded at Dingwalls Dancehall in Camden which featured Gong, Henry Cow, Global Village Truckin’ Co and Grove stalwart Peter Bardens Camel. In the early to mid-70s the Truckers promoted everyone from Uncle Dog and Sandoz to Help Yourself and Kevin Ayers mostly under the motorway on Saturday afternoons.

But the band most associated with free gigs was Hawkwind who came to be the embodiment of 1970s Grove scene – ‘Hawkwind got involved with the underground scene’, says Nik Turner, ‘not through consciously thinking we’d like to be involved…we just were. We liked to play, and I was organising a lot of concerts for the band at the time. For instance, we’d do a gig at Portobello Road under the flyover where Frendz magazine was based. Mike Moorcock and Barney Bubbles were involved in the magazine and Bob Calvert had been writing articles for it…all part of the Underground, which we endorsed and which endorsed us’.

When the Mode of the Music Changes

As the 60s slipped away changes came to the area – the gigantic A40 Westway flyover cut across the Grove at the north end of Portobello Road – casting its shadow of urban alienation. In 1972 the All Saints Hall a cornerstone of the local hip community was torn down. At the same time Emily Young (immortalised in the Pink Floyd hit single) organised the Westway mural project with Arabella Churchill under the gigantic concrete struts of the motorway and the Westway Theatre venue home to many free gigs in the mid 70s was built on the site of the Portobello Green Arcade with seats made from railway sleepers.

For many of its original instigators the Underground began to die irrevocably with the Oz obscenity trial in 1971 and a year later Nasty Tales being busted for similar reasons even if everybody from John Lennon to every Grove band worth their salt did benefits for them. The tone of the music also changed – bands like Stray whose delightful lightly psychedelic ‘Time Machine’ is included here were pursuing a far heavier more turgid direction by then – downer rock was the order of the day.

The drugs had changed – from 1970 onwards cocaine and heroin became much more prevalent – and alcohol which the hippie elite of the 60s had rather scorned was back in favour. Trevor Burton who’d played with the Move and Balls had ended up in West London and briefly joined the Pink Fairies as he recalls ‘I finished up in Notting Hill Gate. I was in a pretty bad way by then, drugs-wise. We’d hit the Mandrax trail and smack had appeared. A lot of smack came from American musicians who were coming in to record at Island and turning people on’. Mick Farren strongly disagrees, ‘this is nonsense. There were junkies in the Grove in the fucking 50s.There was grass (black dealers), pills (everywhere). The cocaine came in when geezers selling the hash had got a taste for a bit of blow for their own use and then it just escalated. And don’t even talk about the mandies and speed. We hardly needed any fucking Yanks to teach us how to get fucked up!’ He also maintains that it wasn’t just the drugs that affected the music, that ‘a bad dose of 1970s reality and hard times’ also took their toll.

The peace and love vibes were getting shorter in supply – the last vestiges of the Underground had taken on a far tougher stance – it was the era of the Baader Meinhof Gang in Germany and here in Britain Jake Prescott and Ian Purdie, and the Angry Brigade, a bunch of anarchists who went straight for the establishment’s jugular bombing the homes of prominent politicians – and of course the authorities clamped down accordingly. Paranoia stalked the streets of the Grove.

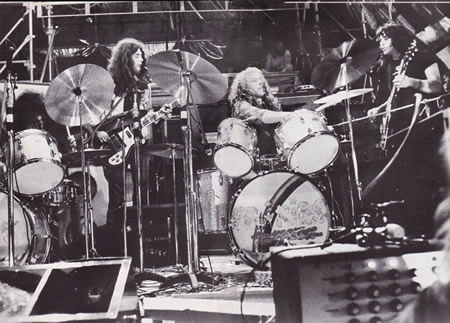

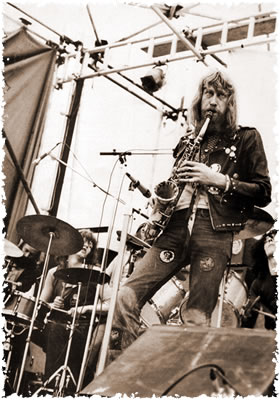

The Pink Fairies [photo above] third LP Kings of Oblivion with Larry Wallis now in the guitar seat eschewed the more Hendrix-inspired psychedelia of its predecessors with a metallic edge worthy of Alice Cooper or the MC5. Wallis a steadfastly good old south London boy brought his own distinctive street vibe along and drinks and drugs seem to be the order of the day if the artwork was anything to go by – whilst the band became less community-bound. They no longer seemed to be doing the Portobello shuffle of yore. A gig in Harlow Park in summer 73 summed up just how excessive the period had become as Wallis remembers, ‘The shortest gig we ever did was in Harlow Great Park. It was fantastic. We were top of the bill, it was a lovely Saturday afternoon, and there were 20 billion people. It was gonna be fantastic There we go. The gear’s all set up and we’re standing around backstage. It’s them, the Pink Fairies. It’s fucking wonderful. Ok here’s the band you’ve all been waiting for – the Pink Fairies. The crowd goes mad. So I get up onstage. “Hello. They say Harlow’s a town. Well, I say, it’s a city! And you’re all City Kids”. It went 1-2-3-4. I look around and Russell Hunter’s flat on his back behind the drums. It all peters out, Russell’s unconscious. He’s taken two Mandrax during the afternoon, drunk himself stupid on Jack Daniels and passed totally out. I never even got to sing one line. That was the end of the gig’.

Bands like the Lightning Raiders and the Warsaw Pakt featuring guitarist Andy Colquhoun (later a Deviant and a Pink Fairy) now began to typify the sound of the Grove - MC5 and proto metal. Yet there was still a close camaraderie amongst musicians during this period – Bob Calvert had joined Hawkwind as lead singer and had also started to make solo LPS, the first of which Captain Lockheed & the Star Fighters , a concept record that featured many of the usual local reprobates including various ex-Fairies and Hawkwind-ers as well as Arthur Brown and Viv Stanshall And the Grove had one more ace up its sleeve – a super group of sorts – Motorhead put together by Doug Smith and featuring very momentarily Larry Wallis and Ian ‘Lemmy’ Killmister who’d been a Hendrix roadie and done time in both Sam Gopal and Hawkwind before being sacked on a North American – if Motorhead was the Grove’s last howl, it was still being heard some 30 years later! Their brand of biker rock is still humungously popular in the new millennium.

Musically speaking the writing was one the wall – in the early 70s Bobby Marley had recorded in Basing Street and his legacy was now in the hands of a new generation of young black Grove-born musicians whilst from his gran’s hi-rise flat overlooking the motorway guitarist Mick Jones together with another Grove face, Joe Strummer who’d led the 101ers laid plans for the Clash.

In a supremely ironic twist Stiff Records – seen by many as heralding the arrival of punk and New Wave - was initially nothing more than the Emperor’s new clothes counting records by Pink Fairies, Motorhead and Larry Wallis (the magnificent ‘Police Car’ included here) amongst its early releases – artwork all courtesy of one Barney Bubbles!

After the Dream Had Faded

By 1978 it was all over – the streets of West London were filled with the sounds of a new generation holding as - Bob Marley put it - their own punky-reggae party.

Though Nik Turner’s Bohemian Love In at the Roundhouse in June ushered out the era in fine style – it might have paid lip service to the oncoming New Wave but the event featured many Grove favourites such as Michael Moorcock, Steve Took and various ex-Hawkwinders including Adrian Shaw who aptly sums it up as ‘the Underground’s last hurrah’.

Farren quit London for New York in 1979. Steve Took died in 1980 choking on a cocktail cherry after a mushroom trip. Barney Bubbles took his own life in 1983. Robert Calvert died of a heart attack in 1988.

However what perhaps nailed the changing zeitgeist best was a poem by the counter culture’s last remaining dog soldier, Mick Farren who’d fought a rear guard action for it all though the 70s – bearing the legend found in a Ladbroke Grove bar, London dated 1978 his poem I Know From Self Destruction seemed to say it all – a street hippie swansong to the Grove’s loss of hope and ideals which Doug Smith had printed up as a parody of Desiderata:

‘Here’s a protest from a juicehead winging straight up from the gutter, to the feeders & the leaders in high offices of power. Like a pigeon from the neon, whose wings and legs are twisted, but can soar just like an eagle when it’s got the motivation.

Yeah, I know from self-destruction it’s a matter of relationship, a private place to head for when you’ve run out of ideas, not a hole to the drag the world in but you’re losing that perspective. And I hear you’ve got a system that kills people & leaves buildings. Is that your best idea – a planet full of buildings?

Yeah I know from self-destruction each and every time it’s lonely; and don’t con me with the sunrise or the flowers of the field. It’s the mafia & the streetcar & the rattle of a taxi; But I want to go on living until I feel like dying

Yeah I know from self-destruction it’s a matter of relationship. It’s the bottom of the bottle & it don’t feel any better if you take the whole world with you. But you’re losing that perspective as they point the cameras at you. It don’t feel any better if you leave behind a waste land & spreading global twilight will never make you godlike.

I know from self destruction it’s a very private matter. So if you want to make an exit you better take up drinking or go & join the junkies ‘cause I ain’t going with you, to bolster your grandeur and feed your sense of power

I like the life I’m living even if it’s in the gutter. And the city don’t take prisoners & I’ll choose my time of dying let no man choose it for me, ‘cause I know from self destruction. Yeah I know from self destruction’.

Nigel Cross July 2007. Artwork & production: Phil McMullen

Select Bibliography and Photo Credits:

Joe Boyd White Bicycles: Making Music in the 1960s Serpent’s Tail, 2006 Carol Clerk, The Saga of Hawkwind, Omnibus Press, 2004 Mick Farren Give the Anarchist a Cigarette Jonathan Cape, 2001 Mick Farren & Edward Barker Watch Out Kids [picture above] Open Gate Books, 1972. Cover art for 'Watch Out Kids': David Wills (David maintains a Barney Bubbles blog, which is located at http://davidwills.wordpress.com/ ) Jonathon Green All Dressed Up: Sixties and the Counter Culture, Jonathan Cape, 1998 Jonathon Green Days in the Life: Voices from the English Underground, 1961-71 Heinemann, 1988 Barry Miles In the Sixties Jonathan Cape, 2002 Jeremy Sandford & Ron Reid, Tomorrow’s Children, Jerome Publishing, 1974 Ptolemaic Terrascope magazine, edited by Phil McMullen, 1989 - 1992 Zig Zag magazine, edited by Pete Frame, issue 11 1972

The full line-up of the album is as follows (NB the dates shown are publishing dates rather than release dates):

Edited by: Phil McMullen for Terrascope Online, August 2007 - 08.

Reproduced with kind permission. Many thanks to Nigel Cross, Marc Beard (project manager at Sanctuary), and Christina West for help with the photos. © Terrascope Online, 2007 |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

However, the label

which most of all embodied the ethos of this period was Head

started by John Curd who’d later become successful as one of

the capital’s biggest live gig promoters. It may have had

its office in the West End, but Head’s heart was in the

Grove and amongst its first signings were both the Village

(whose ‘Man in the Moon’ is also included here) and Mighty

Baby whose ‘House with out Windows’ from their debut LP

again is part of this set. Tragically Curd was busted for

dealing in the summer of 1970 leaving Mighty Baby high and

dry just to prior to the release of a projected second LP

The Day of the Soup and also new signings Quiver who

were about to release their debut 45 with the company – ‘The

Ballad of Barnes County’ and ‘Gone in the Morning’, a later

version of which is featured here from their second Warners

LP.

However, the label

which most of all embodied the ethos of this period was Head

started by John Curd who’d later become successful as one of

the capital’s biggest live gig promoters. It may have had

its office in the West End, but Head’s heart was in the

Grove and amongst its first signings were both the Village

(whose ‘Man in the Moon’ is also included here) and Mighty

Baby whose ‘House with out Windows’ from their debut LP

again is part of this set. Tragically Curd was busted for

dealing in the summer of 1970 leaving Mighty Baby high and

dry just to prior to the release of a projected second LP

The Day of the Soup and also new signings Quiver who

were about to release their debut 45 with the company – ‘The

Ballad of Barnes County’ and ‘Gone in the Morning’, a later

version of which is featured here from their second Warners

LP.

Unlike the others

Wayne had worked his way up through a more traditional Tin

Pan Alley route and knew the music biz well – he’d latterly

been working for the Beatles Apple Publishing and was

managing High Tide, a super heavy very psychedelic quartet

featuring ex-Misunderstood guitarist Tony Hill whom he had

got signed to Liberty. As Doug puts it, ‘Wayne was the man

because he knew most of the people in the music business, he

was so well connected, he knew Drummond, Peel, Simon Stable

and many of the alternative figures’.

Unlike the others

Wayne had worked his way up through a more traditional Tin

Pan Alley route and knew the music biz well – he’d latterly

been working for the Beatles Apple Publishing and was

managing High Tide, a super heavy very psychedelic quartet

featuring ex-Misunderstood guitarist Tony Hill whom he had

got signed to Liberty. As Doug puts it, ‘Wayne was the man

because he knew most of the people in the music business, he

was so well connected, he knew Drummond, Peel, Simon Stable

and many of the alternative figures’.

originally

from the south coast who’d rode the blues boom and early

prog era with two albums for CBS (check out their track

‘Autumn Song’ featured here) but who had started to take on

a style more redolent of the great San Francisco bands like

Quicksilver – drummer Mick Bradley talked to ZigZag

magazine about life there back in 1971: ‘we lived in Oxford

Gardens, just off Ladbroke Grove for a while. I wouldn’t say

it was creative at all, but it had a family atmosphere about

it all right. You walked out and you felt that you were part

of a community. But I don’t think it’s true any more because

most of the people living there just lie about in their

rooms stoned. There are still a few good bands down there,

but it’s not a particularly enlightened part of the world or

anything like that’.

originally

from the south coast who’d rode the blues boom and early

prog era with two albums for CBS (check out their track

‘Autumn Song’ featured here) but who had started to take on

a style more redolent of the great San Francisco bands like

Quicksilver – drummer Mick Bradley talked to ZigZag

magazine about life there back in 1971: ‘we lived in Oxford

Gardens, just off Ladbroke Grove for a while. I wouldn’t say

it was creative at all, but it had a family atmosphere about

it all right. You walked out and you felt that you were part

of a community. But I don’t think it’s true any more because

most of the people living there just lie about in their

rooms stoned. There are still a few good bands down there,

but it’s not a particularly enlightened part of the world or

anything like that’. Barney

Bubbles

Barney

Bubbles

In

1970 the weekend before the Carnival, Hawkwind [pictured

left] played a free

gig on Wormwood Scrubs with Quiver – nearly scuppered by

skinheads from nearby Queens Park, the space rockers won

over both the local freaks and the bovver boys - and the gig

was to be their coming out party – up until then they’d not

been taken seriously yet from mid 72 when their 45 ‘Silver

Machine’ hit the charts, they’d take the anarchistic spirit

of the Grove to all corners of England, and eventually

America.

In

1970 the weekend before the Carnival, Hawkwind [pictured

left] played a free

gig on Wormwood Scrubs with Quiver – nearly scuppered by

skinheads from nearby Queens Park, the space rockers won

over both the local freaks and the bovver boys - and the gig

was to be their coming out party – up until then they’d not

been taken seriously yet from mid 72 when their 45 ‘Silver

Machine’ hit the charts, they’d take the anarchistic spirit

of the Grove to all corners of England, and eventually

America.