alactic

Ramble is the latest (and, perhaps, best) in a

long line of music books designed to tease and tantalise the appetites of

the most jaded musicologist. Inspired by Patrick Lundborg’s groundbreaking

2006 Acid Archives book of obscure ’60s and ’70s US and Canadian

underground music, editor Richard Morton Jack invited Lundborg, his fellow

Acid Archivist, Aaron Milenski, and other "music fans and experts",

including Tenth Planet founder David Wells and leading jazz expert Tony

Higgins to close a perceived gap in British music analysis.

alactic

Ramble is the latest (and, perhaps, best) in a

long line of music books designed to tease and tantalise the appetites of

the most jaded musicologist. Inspired by Patrick Lundborg’s groundbreaking

2006 Acid Archives book of obscure ’60s and ’70s US and Canadian

underground music, editor Richard Morton Jack invited Lundborg, his fellow

Acid Archivist, Aaron Milenski, and other "music fans and experts",

including Tenth Planet founder David Wells and leading jazz expert Tony

Higgins to close a perceived gap in British music analysis.

Jeff Penczak sat down with Jack, co-founder of the Sunbeam reissue label and a former contributor to Ptolemaic Terrascope, to discuss his latest project..

How did you come up with the idea for such a massive undertaking?

It had bugged me for a while that no such book already existed, as there was such a huge number of albums from the 1960s and 70s that had never been written about, and so much hype and misinformation circulating about them (typically perpetuated by dealers and eBay sellers). Then, in 2006, Patrick Lundborg published his groundbreaking Acid Archives book, reviewing obscure US and Canadian underground music from the 60s and 70s, which paved the way for Galactic Ramble.

There are a few books on the market which concentrate on reviews / analysis, as opposed to Vernon Joynson’s encyclopedic approach with his Tapestry Of Delights. I’m thinking of books like The Mojo Collection, to which you also contributed. Tell us how your book differs from those others.

The principal way in which Galactic Ramble differs from other critical works on the subject is its scope – no such book can ever be truly comprehensive, but this one comes closer than anything yet published. I also tried to make it build on the work done by Vernon Joynson and a few others by including information such as precise release dates and details of inserts, posters etc that were given away with records. Finally, it’s the first book covering that period to include original reviews alongside modern ones.

The decision to include excerpts from contemporary reviews is brilliant and certainly makes the tome stand apart from similar offerings, some of which are listed in your “Suggested Reading List”. How did you ever locate all those back issues of Disc & Music Echo, Beat Instrumental, Sounds, and, of course, Melody Maker, Record Mirror and NME?

The short answer is, by slowly and painstakingly building up a library of them. I had a couple of strokes of luck, in that Tim Rice gave me his collection, and I found a record store here in the UK that had a huge pile of music papers for a pound each. But individual issues of certain papers can sell on eBay for £200, so it’s a slow process finding them for the right price. Incidentally, I find it remarkable that so little rock journalism draws on these old papers. Instead, the vast majority of rock writers rely on each other’s work, which means that masses of interesting interviews and so forth go untapped to this day, and errors are repeated ad infinitum. [long-time readers will no doubt recall that a regular feature of the Ptolemaic Terrascope for several years was the inclusion of 4 page "Scrapbooks" of 1960s/70s cuttings and reviews - Phil]

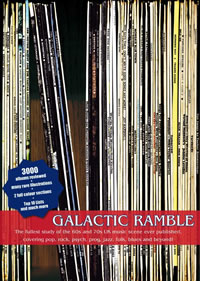

Are those your albums that grace the cover? An impressive collection indeed, but why did you intentionally omit some well-known ringers that might have attracted a wider audience? Was there a concern that people might be hesitant to pick up a book that appears to cover obscure acts that non-collectors might be unfamiliar with?

The albums on the cover are indeed mine… though records in my collection tend to come and go depending on how often I listen to them and how much someone else wants them! The cover is an A-Z taken from left to right, and I thought it would be more fun to make it up of rarities and obscurities rather than Beatles and Stones etc. I hope that won’t scare people off, as of course all the well-known acts are in the book too.

Let’s talk about the content.

You walk a fine line

between

appealing to the mainstream music fan and the collector market. Alongside

the Beatles, Kinks, Stones, and Who entries, there are perhaps twice as many

artists that aren’t well-known outside the collectors’ stalls, so how would

you describe your target audience for the book?

between

appealing to the mainstream music fan and the collector market. Alongside

the Beatles, Kinks, Stones, and Who entries, there are perhaps twice as many

artists that aren’t well-known outside the collectors’ stalls, so how would

you describe your target audience for the book?

The book, needless to say, reflects nothing more or less than what was actually released back then. Of course there were many more misses than hits, so that means there are more obscurities in the book than household names. The target audience for the book is as broad as possible, though. I was determined for its tone not to be snobbish. I would compare it to a film guide – the well-known and the obscure sit side by side, and hopefully most readers will find it of interest for the things they already know, and of use if they want to dig deeper. I also wanted to include the mass of privately-pressed albums that appeared in the 60s and early 70s, which are obscure by definition, but often better than major-label releases.

Tell us a little about your remit. You have elected to concentrate on 1963-73 (occasionally outstepping your boundaries). What was so special about that period in British music?

Rock music was brand new in 1963 (Please Please Me, which some regard as the beginning of the rock album as we know it, was issued in March), and it evolved very rapidly, as did pop culture alongside it. Thus the period between 1963-73 witnessed countless innovations and permutations of the album, with new genres and approaches springing up the whole time. From Gerry & The Pacemakers to Roxy Music is an amazing leap in such a short time! Secondly, as sales of LPs began to outstrip that of 45s in the late 60s, more and more albums got released, urging musicians to be more and more creative. Some might say that by 1973 popular music had begun to cannibalise and regurgitate itself – which isn’t to say that great albums weren’t still being made (and, of course, they still are), but that everything it could say already had been, by someone somewhere, however obscure. Also, I had to cut off somewhere, so a decade seemed a sensible period to focus on.

Besides the standard genres of rock, prog, folk, and blues, you’ve also included quite an extensive list of jazz artists. Why the decision to step into the jazz world in a predominantly rock-oriented book?

I think that jazz and rock have been regarded as mutually exclusive for too long. In Britain, at least, the two genres endlessly crossed over in the 60s and 70s. Great jazz musicians played on rock records, and a lot of supposedly ‘rock’ musicians were rooted in jazz (Jack Bruce, Ginger Baker, Jon Hiseman, Brian Auger and many others spring to mind). So I was trying to encourage rock fans to explore jazz more, and vice versa. Secondly, a huge amount of terrific British jazz albums have still never been properly acclaimed or reissued, so I wanted to do my little bit to raise their profile.

The tone of the reviews is very colloquial, as if you recorded a conversation among musicologists down the local pub. Was this an attempt to avoid the stuffy academia that can often slip into projects of this type?

I don’t think writing about popular music should ever be dry, and certainly not in a reference book – pop writing isn’t an academic exercise, it’s all about conveying enthusiasm. I can’t stand pompous, pretentious music journalism, or people who talk about, say, Johnny Rotten as if he were Hegel or Kant. And, as editor, I had the luxury of only approaching writers whose style and taste would fit within my view of how the book should be!

Written and directed by Jeff Penczak. Artwork and edit: Phil McMullen. With Gracious! thanks to all involved.

Our review of 'Galactic Ramble' is published here:

http://www.terrascope.co.uk/Reviews/Reviews_July09.htm#GalRamb

For more information about the publication, visit here http://galacticramble.com/

or drop a line to here info@foxcotebooks.com